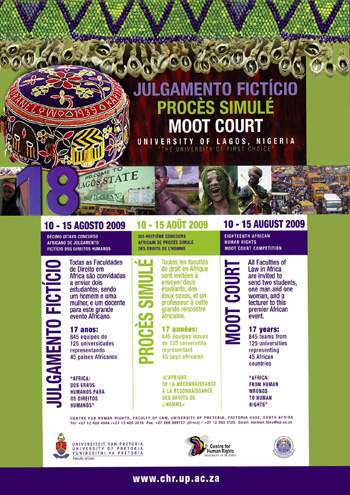

Eighteenth African Human Rights Moot Court Competition

Lagos, Nigeria, 10 - 15 August 2009

During the week of 10 to 15 August 2009, students and faculty representatives representing 70 law faculties from 26 countries across Africa, assembled in Lagos, Nigeria for the 18th African Human Rights Moot Court Competition. The event was organised by the Centre for Human Rights, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, in collaboration with the University of Lagos (UNILAG). The competition simulated the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, which was recently established by the African Union for the African continent. The theme this year was arguing the rights for minority groups as enshrined in the African Charter.

The Competition was officially opened in the main Auditorium of the University of Lagos, by Nigeria’s Attorney-General, Justice Chief Michael Kaase Aondoakaa on behalf of Nigeria’s Vice-President, Goodluck Jonathan. UNILAG’s Department of Dramatic Arts entertained the audience with an exhilarating performance of music, dance and drama, centered on a human rights theme.

The four preliminary rounds were conducted in French, English and Portuguese over two days in the lecture rooms of the Faculty of Humanities, with each team arguing in a separate court in their own language before panels of judges comprised of faculty representatives. Each team was required to argue twice for the Applicant and twice for the Respondent. Thursday was allocated to relaxation. Students and faculty representatives were treated to a visit to the Oba’s Palace in Lagos where they met with His Royal Majesty Alaiyeluwa Oba Riliwanu Babatunde Osuolale Aremu Akiolu, the Oba of Lagos, who welcomed them and took them on a tour of the palace. Then the entire group headed for Akoda beach where they had lunch and relaxed playing a variety of games on the sand before being attracted to the dance floor by the throbbing African music.

Friday and Saturday kept everyone very busy. The audience was entertained by performances by short-listed candidates who had submitted scripts in English, French and Portuguese. The Conference on International Law and Human Rights Litigation in Africa also took place, with papers being presented by a large number of delegates from across the continent. In addition, a training course was presented for International Law in Domestic Courts (ILDC) reporters and those interested in becoming ILDC reporters.

The highlight of the week, however, definitely took place on Saturday, 15 August, in the main Auditorium of the University of Lagos, when the top two English teams, the top two French teams, and the top two Portuguese-speaking teams merged to form two new combined teams of six students each in the final round. Justice Muhammadu Lawal Uwais, former Chief Justice of Nigeria, presided over a panel of eminent jurists which included Justice Awa Nana Daboya, President of the Court of Justice of ECOWAS, represented by Mr Yusuf Danmadami, Advocate Reine Alapini Gansou, Member of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, Prof Mamadou Badji, Director of the Centre des Relations Internationales et de la Francophonie, Mrs Ayo Obe, Member of the Board of the Open Society Initiative for West Africa, and Dr David Padilla, Former Assistant Executive Secretary, Inter-American Commission on Human Rights In a closely contested final round, the team appearing for the Applicant, viz., the University of Ghana, the University de Dschang from Cameroon, and Eduardo Mondlane University from Mozambique, were declared the winners. The Respondents and runners-up were represented by the University of Cape Town, Gaston Berger de St Louis of Senegal, and the University of Zambeze from Mozambique.

The week’s proceedings were concluded on Saturday evening with a banquet at the Sheraton Hotel and Sunday, 16 August, saw everyone heading for home, with friendships having been forged and contact details exchanged. The general consensus was definitely that the 18th African Human Rights Moot Court Competition had been a major success.

Hypothetical Case

1. The Republic of Kuramo (Kuramo), a country on the west coast of Africa, gained independence from Halifax on 1 July 1962. Kuramo is divided into four administrative units, namely the Southern, Northern, Eastern and Western Provinces. Kongi City is the capital of Kuramo’s Eastern Province. Kuramo borders the Democratic Republic of Bamalus (Bamalus), also previously colonized by Halifax. Both states became members of the United Nations (UN) soon after independence. The capital city of Bamalus is Bama City, which also constitutes one of the five administrative units of the country. Bama City is situated immediately adjacent to Kongi City, on the coast, divided only by the Crocodile River. The present population of Bama City is about 800,000, while that of Kongi City is about 200,000, almost exclusively members of the Kongi group. The total population of Kuramo is about 10 million; and that of Bamalus about 12 million people. The Kongi is the smallest ethnic group in Kuramo. Bamalus has claimed since its independence in 1965 that it is the rightful sovereign of Kongi City. In 1984 Bamalus invaded and occupied Kongi City for two months before withdrawing. During the occupation there was a reign of terror in which thousands of Kongi lost their lives.

2. Long before independence, the area now constituting Kongi City and Bama City served as trading zones between local inhabitants and colonial traders. The Bama City area was originally inhabited by the Bama ethnic group. Although the Kongi and Bama languages are quite distinct, the people of the two territories shared most of their customs and traditions. They have traditionally mainly been fishermen and hunters, and had close affinity to nature and the environment. After independence, the Bama developed much faster than the Kongi, mainly as a result of numerous schools being built in Bama City, and the settlement of other groups in that area. Today, Bama City is a very multi-ethnic and industrialised city. Bama identity has largely disappeared, mainly as a result of the government’s policy of assimilating all groups as part of the nation-building process. By contrast, Kongi City is a mono-ethnic and largely ‘peri-urban’ settlement, where many people still practice their traditional culture and modes of production such as fishing and hunting in the adjacent hills. In the Preamble to the Kuramo Constitution, the Kongi is recognised as a ‘vulnerable minority’.

3. The mainstay of the Bamalus economy is minerals like gold, diamonds and tin. Its per capita GDP for 2008 was officially estimated at $ 1200. With the assistance of the Haliff International Oil Services Company Limited (Haliff Ltd) (West Africa) (Haliff Ltd WA), a local subsidiary of a private company registered under the laws of Halifax and with its headquarters in Halifax, Bamalus also recently started exploiting oil and gas reserves in the area around Bama City. Bamalus holds a 45% share of Haliff Ltd WA. Depending for its survival mostly on agriculture and limited tourism, and with an officially estimated per capita GDP of $ 690 for 2008, Kuramo is a much poorer country. The recent explorations by Haliff Ltd WA revealed that there may be oil and gas deposits in the Eastern Province of Kuramo, especially in and around Kongi City. Efforts by Haliff Ltd WA are on-going to determine if these are sufficient for commercial exploitation. Some international newspapers have reported that the explorations are starting to affect the natural environment around Kongi City.

4. Both countries have enacted a Bill of Human Rights, similar in substantive rights to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), as part of their respective Constitutions. They have also both been state parties to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights since 1987. In 1977, Kuramo and Bamalus entered into a ‘Bilateral Crimes and Transnational Prosecution Treaty’, allowing for extradition of ‘all serious crimes’ between the two countries which was ratified by the parliaments of Kuramo and Bamalus. Kuramo also ratified the following AU instruments: the amended African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (2003), the Protocol to the African Charter on the Rights of Women in Africa (in 2005), the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (in 2003), and the Protocol to the African Charter on the Establishment of an African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (on 10 December 2007, having signed the Protocol on 10 December 2006). Kuramo is also a state party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). Kuramo has signed but not ratified the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

5. Section 1 of the Kuramo Constitution provides that ‘the Constitution of Kuramo is supreme and anything in any law, conventions, protocols, or regulations shall to the extent of its inconsistency, be void’. All international instruments which Kuramo has ratified have been domesticated by virtue of the ‘International Instruments and Conventions (Ratification and Domestication) Act of 1987’. The Federal High Court of Kuramo is the highest court in the country.

6. Early in 2005, Bamalus filed a petition against Kuramo before the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Kuramo made a declaration accepting the jurisdiction of the Court. The sole issue before the ICJ was whether Kongi City falls within Kuramo or Bamalus. According to undisputed tradition the Bama chief Onikoko concluded an agreement at the beginning of the 19th century with Kola, the chief of the territory across the Crocodile River, in which Kola ceded part of his territory, known today as Kongi City. The agreement was concluded to enable the Bama to withstand external aggression. Relying on the agreement, the ICJ in December 2005 ruled that Kongi City had been annexed to Bama City by virtue of the agreement, and that it therefore belongs to Bamalus. The ICJ ordered that Kuramo must, by 1 January 2007, transfer the territory of Kongi City to Bamalus. Immediately after the judgment, the Kuramo government declared that it would refuse to give effect to determination of the ICJ. The late Chief Alfred Cole migrated from Bama City to Kongi City in the 1920s. Under Kongi custom, the traditional ceremony called ‘Iwale’, meaning ushering, was the only requirement for admitting a stranger who offered to become a member of the Kongi community, provided the person had lived in the community for not less than 10 years and demonstrated evidence of good communal living. In 1935, the late Chief Alfred Cole was admitted as a member of the Kongi community, by way of ‘Iwale’, with full privileges and benefits. He lived and carried on his business in Kongi City until his death in 1972. However, he never formally acquired Kuramo citizenship. Wale Cole was born in Bama City to one of Chief Cole’s wives, in 1959. Wale later joined his father in Kongi City, and went to study law in the University of Dalton in the Northern region of Kuramo. He was a vocal member of the Dalton Student Union, especially on the issue of the rights of gay and lesbians, arguing that the dominantly Muslim society of the Northern region should accept or at least tolerate them. A rumour started going around that he was involved in a sexual relationship with another male student.

7. Upon graduating with distinction in 1984, Wale set up a law firm in Kongi City called ‘Amity Chambers’. He also pioneered the formation of the Kongi Peoples’ Movement (KPM), which was established in 2001. According to the Constitution of KPM, its objectives are not only to ‘advance the development and protect the human rights of the Kongi minority in Kuramo’, but also to ‘promote and protect the rights of all minorities, including sexual minorities’. In the Constitution, the term ‘member of a sexual minority’ is defined as ‘anyone whose sexual orientation either exclusively or partially predisposes a person to a member of the same sex’. At the time of its formation, an attempt was made to register KPM under the Non-Profitable Organisations (Registration) Act. The Registrar denied the application on the basis that that registration would be impossible as it conflicts with Kuramo’s anti-sodomy laws. Article 7(2) of the Kuramo Penal Code outlaws ‘sexual relations between persons of the same sex’, and prescribes the imposition of a sentence of between 2 and 7 years imprisonment upon conviction. Although none of its members have been arrested, KPM remains unregistered up to this day and functions mainly ‘underground’.

8. Early in 2006, the Kuramo government changed its position on the ICJ’s judgment. According to the Attorney-General (AG), the main reason for this reversal was a full appreciation of the fact that Kuramo had consented to the ICJ’s jurisdiction. In order for the country to maintain its international reputation, the AG argued in a television interview, it had to comply with the order. In addition, he revealed that Haliff Ltd WA, which has exclusive rights to conduct the exploitation of resources in Kuramo, entered into an agreement with the Kuramo government to pay 49% of all future profits from any oil or other minerals found in the Kongi City area to the Kuramo government.

Following this change in the government’s position, KPM members resolved at a general meeting that the Movement should deploy every effort to resist Kuramo’s ceding of Kongi City pursuant to the decision of the ICJ. KPM also resolved to file an application in its own name before the Federal High Court of Kuramo to ‘restrain the government, its organs, agencies or departments from ceding Kongi City to Bamalus pursuant to the decision of the ICJ’. Before the Court, KPM also raised the government’s refusal to register it, arguing that it was a violation of its right to freedom of association guaranteed in the Kuramo Constitution. Declining the invitation to decide on this issue, the Court left the matter pertaining to the registration open, but found that the substantive issues raised needed the Court’s engagement irrespective of whether KPM was registered or not under the relevant Act.

9. On 23 June 2006, the Federal High Court of Kuramo found in favour of KPM and held as prayed. The AG of Kuramo publicly contested the correctness of the Federal High Court’s decision, on the basis that KPM did not have locus standi to bring the application. Some time thereafter, in November 2006, members of the Kuramo government attended a final consultative meeting between Bamalus and Kuramo, in collaboration with the UN Secretary-General, to work out the peaceful transfer of Kongi City to Bamalus.

10. In view of the position adopted by the Kuramo government, KPM and its members resolved to employ all necessary means to resist the ceding of the Kongi City area to Bamalus. In early December 2006, a group of youths invaded Haliff Ltd WA operations in the Kongi City area and damaged its vital equipment. In a televised statement, the youths contended that it was Haliff Ltd that ‘unfairly persuaded the government into honouring the ICJ decision ceding the Kongi City territory to Bamalus’. The youths also killed two Halifax nationals, who were workers of the company, and escaped with cash in the sum of $200,000.00. They also seized two other workers as hostages, and demanded ransom in the sum of $1 million for each of the workers and the immediate cessation of explorations in their community.

11. Two days after the attack, on 7 December 2006, the Federal Police of Kuramo Republic (FPK) invaded Kongi City, killing about a thousand people, mainly women and children and a few elderly people. The Chief of the FPK regretted these killings, but stated that they occurred because the community resisted its efforts to find the ‘elements responsible for the atrocities committed against the Halifax nationals’. Television footage showed members of the community, gathered together in masses, hurling stones and self-made petrol bombs at the FPK. The FPK also declared Wale a wanted person. In a broadcast on the state radio station, the Inspector-General of the Federal Police (IGFP) alleged that ‘preliminary investigations revealed that “a homosexual immigrant” is the mastermind of the recent attacks, killings, stealing and kidnapping of personnel and equipment of Haliff Ltd WA in the Kongi City region’. The IGFP offered a reward of $50,000 for anyone with useful information about the whereabouts of Wale Cole.

12. In the morning following the broadcast of the IGFP, Wale appeared at the Federal Police Headquarters in Kongi City contending that he was not a criminal and was never on the run. Immediately upon his appearance, the IGFP directed that he be detained in police cells, pending a decision of the Minister of Police Affairs and Internal Security or the AG whether to prosecute him in the Republic or deport him with a request for prosecution in his country of origin, Bamalus, pursuant to Bilateral Crimes and Transnational Prosecution Treaty. Extradition proceedings proved difficult and stalled. After habeas corpus proceedings, instituted on Wale’s behalf, succeeded, he was released on 21 February 2007. A week later, he was re-arrested and held in the awaiting-trial prisoners’ section of Kongi City prison. In a press statement, the AG stated that Wale Cole was being detained under the Enemy Combatant (Federal Police Discretion) Act of the Kuramo Republic 1984. Section 7 of this Act allows the detention without trial of anyone suspected on reasonable grounds to endanger public safety and national security for renewable periods of ninety days. After the expiry of ninety days, the detention of a suspect may only be prolonged if a judge, sitting in camera, so decides, on evidence provided to him by the national security agencies. After his re-arrest, Wale Cole’s detention has been prolonged time and again by different judges, in line with the prescribed procedures. He remains in detention up to this day. He never raised any complaints about the material or psychological conditions of detention to the observers of the ICRC which have regularly visited him.

13. On 1 January 2007, acting on the directive from the President, the national flag of Kuramo was lowered in Kongi City. However, the people of the community insist that they will not accept the authority of any officials of Bamalus. The Home Affairs Office of Bamalus then started to distribute pamphlets to all inhabitants of Kongi City, informing them that they must either accept to be part of Bamalus, or leave its territory within 7 days. With very few exceptions, all the inhabitants stayed on in Kongi City, and continued their protests. Due to these continuing protests, Bamalus never exerted its authority over the territory. To fill the void, Kuramo retained legal and administrative authority. Haliff Ltd WA continued to undertake explorations in the Kongi City area, under heavy security provided by the Kuramo government.

14. Meanwhile, Wale’s detention continued. In June 2007, a group of lawyers who graduated from the law faculty of University of Dalton teamed up to challenge his continued detention. They argue that Wale’s detention is contrary to the Constitution and international law. In September 2007, the group instructed a leading lawyer in Kuramo, Jude Law, who filed an action in the Federal High Court in Kongi City, seeking leave of court for the enforcement of fundamental human rights under Fundamental Human Rights (Enforcement Procedure) Rules of Kuramo Republic 1982.

15. At the time of hearing of the application for leave to enforce fundamental human rights, in January 2008, counsel to the respondent, the AG, filed a motion for preliminary objection. The ground of the objection is that section 23 of the Combatant (Federal Police Discretion) Act ousts the court’s jurisdiction to hear an application based on the enforcement of fundamental human rights of a person or persons detained pursuant to the Act. In its ruling, dated 21 July 2008, the Court upheld the submission of the respondent, and held that by virtue of section 23 of the Enemy Combatant (Federal Police Discretion) Act of Kuramo Republic 1984, it lacks the jurisdiction to hear and determine the application of Wale seeking leave to enforce his fundamental human rights. 16. Dissatisfied with the ruling of the High Court, KPM immediately submitted a complaint against Kuramo to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Commission), through an international NGO based in London, called ‘Green Advocates’ (GREA), seeking the following relief:

i) a declaration that implementation of the ICJ’s decision on Kongi city by Kuramo amounts to violation of the rights of the Kongi people under the African Charter and international human rights law;

ii) a declaration that the continued detention of Wale without trial violates the African Charter and other international human rights law, and compensation for the hardship he had suffered;

iii) a declaration that the invasion and killing of people of Kongi City, mainly women, children and old persons, by the Federal Police amounts to genocide or is otherwise in conflict with the African Charter and international human rights law, and compensation to the families of those killed;

iv) a declaration that the refusal to allow KPM to register violates the African Charter and international law.

17. At its November 2008 session, the African Commission declared these matters admissible, and referred the case to the African Court for its decision. Instruction: Prepare arguments on behalf of (1) the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (which prepares and argues the case on behalf of the applicant) and (2) the Government of the Republic of Kuramo on (a) the admissibility and (b) the merits of each claim to be argued before the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights. The case has been set for hearing in August 2009.