21 March 2023

The theme of 2023 Human Rights Day is ‘Leave no one behind’. This phrase is a pillar of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It highlights that discrimination has a legal dimension, but emphasises that exclusion and maginalisation is also material. It is in the first place people who live in conditions of poverty who are ‘left behind’ in South Africa. Unemployment is sky high, especially among the youth. Almost 40 percent of South Africans experience some form of food insecurity.

Socio-economic rights

The years of COVID-19 revealed the fissures in our society. COVID-19 left many behind, because they experience poverty on a daily basis, including hunger and a lack of access to quality health care, and being exposed to higher likelihood of infection due to living in densely compressed informal settlements.

The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996, was devised as a transformative document. It treaded new ground by making an extensive list of socio-economic rights justiciable before national courts. There are countless examples of socio-economic rights being vindicated through litigation. However, there are also criticism against the courts judgments. Of late, the enthusiasm and fervour to litigate socio-economic rights cases appears to have dwindled.

It is the primary obligation of the government to put laws and policies in place that aim to realise the socio-economic rights of South Africans. This task cannot be left to the courts. Litigation is piecemeal, and poorer people are likely to experience difficulties accessing constitutional remedies.

For this reason, section 184(3) of the Constitution provides for a scheme in terms of which realising socio-economic rights is a routine and cross-cutting responsibility of all government departments. Under this provision, the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) must on an annual basis require relevant organs of state to provide it with information on the measures that they have taken towards the realisation of the rights in the Bill of Rights, concerning housing, health care, food, water, social security, education and the environment.

While the SAHRC has for a number of years made efforts to implement this provision, the process has been a challenge, mainly due to the inaction and lethargy of the executive at the various levels in providing the required information. Completed reports were also not subjected to parliamentary scrutiny and critical discussion. In recent years, no comprehensive report on the ‘status of socio-economic rights’ has seen the light of day.

The SAHRC should prioritise, in the next year ahead, the implementation of section 184(3). It should recommit itself, and secure high-level political support for the re-invigoration of this process.

Persistent racism, hate crimes and hate speech

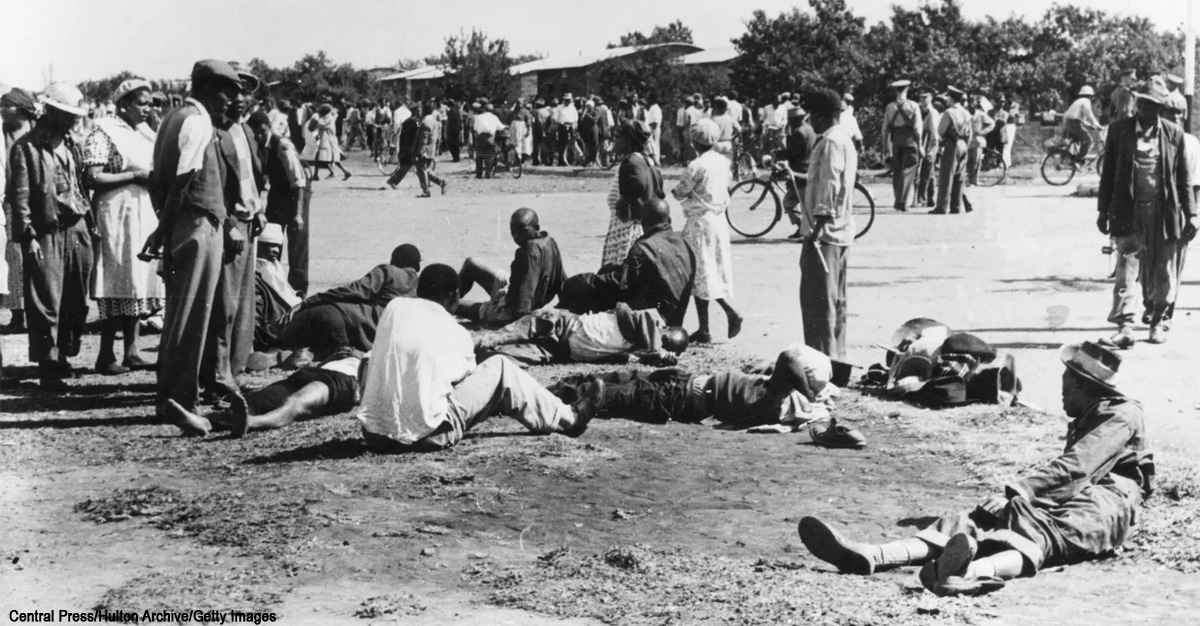

On 21 March 1960, 69 protestors were killed and 180 injured when police opened fire at a crowd of peaceful protestors in Sharpeville. They were protesting apartheid pass laws which were used to limit the movement of the majority of South Africans. The Sharpeville massacre marked a turning point in the struggle against apartheid. Sixty-three years later, we continue to commemorate the lives lost on that day.

Despite the promises of the Constitution, patriarchy, sexism, ableism, homophobia still permeate our society. Hate speech and hate crimes are also still features of the South African landscape.

The Centre therefore welcomes the adoption by the National Assembly of South Africa of the Prevention and Combating of Hate Crimes and Hate Speech Bill on 15 March 2023. This law introduces hate crimes and hate speech as offences. A hate crime is an offence committed based on a person’s prejudice or intolerance to the victim’s age; albinism; birth; colour; culture; disability; ethnic or social origin; gender or gender identity; HIV status; language; nationality, migrant or refugee status; race; religion; sex, which includes intersex; or sexual orientation. Hate speech is the intentional publication or communication in a manner that could reasonably be construed to demonstrate a clear intention to be harmful or to incite harm; or to promote or propagate hatred, based on any one or more of the grounds mentioned above.

However, the Bill is not yet law. It still has to be passed by the National Council of Provinces, and then signed into law by the President. The Centre calls for an acceleration of this process.

Xenophobia

The CHR is concerned with the fear, hatred and hostility towards foreigners which has in many ways culminated in acts of discrimination and violence. The prejudices and hostile attitudes towards foreigners in South Africa contradict the values of unity entrenched in the Constitution, in accordance with section 9, which states that everyone is equal before the law and is thus entitled to the same rights and enjoyments regardless of nationality.

It is disturbing that some political leaders in South Africa have made inflammatory statements which tend to perpetuate xenophobic sentiments. The Minister of Home Affairs, Dr Aaron Motsoaledi suggested that the time for diplomacy was long gone as SA’s ubuntu was being abused by individuals who are criminals in their own countries. Former South Africa Transport Minister, Mr Fikile Mbalula, made remarks suggesting that “illegal foreigners” are a contributing factor to high unemployment in the country.

Further, the Department of Home Affairs and relevant line Ministries have put in place policies that restrict access to employment, health and education for foreign nationals.. The establishment and free operation of vigilante movements such as Operation Dudula have worked to further entrench xenophobia by blaming foreign nationals for the economic strain and social ills in South Africa. This is reminiscent of apartheid-era South Africa where native South Africans were targets of discrimination. Some South African citizens are blaming foreign nationals for increased inequality and poor access to services, failing to recognise that these inequities are a product of apartheid-era South Africa.

Violence against women

One of the most salient human rights challenges currently facing South Africa, referred to by President Cyril Ramaphosa as South Africa’s ‘second pandemic’ , is the increasing rates of violence against women, prominently presented in the form of gender-based violence and femicide (GBVF). By the end of 2022, GBVF was recorded in South Africa at five times the global average..

The CHR applauds the recent launch of the national strategic plan on GBVF with its primary vision being to create a nation free from violence directed at women, children, and the LGBTQIA+ community. However, this vision, focusing on the infringement of women’s rights, will only become a reality in South Africa when women start to feel safe enough to walk around alone in their own communities. This vision will also be realised when stakeholders such as the National Council on Gender-based Violence and Femicide, the Department of Women, Children and Persons with Disabilities in the Presidency and the Commission of Gender Equality jointly collaborate with civil society to confront the challenges.

A government closer to the people

The protest marches of 20 March foregrounded the need for government at all levels to be closer to the people through dialogue and community outreaches. Government must have compassion for the vulnerable and marginalised communities and combat the triple burden of inequality, unemployment and poverty affecting citizens and immigrants and act to the best of its ability to make real the promises of the Constitution.

For more information, please contact:

Centre for Human Rights

Tel: +27 (0) 12 420 3228

Fax: +27 (0) 86 580 5743

frans.viljoen@up.ac.za

Centre for Human Rights

Tel: +27 (0) 12 420 3810

Fax: +27 (0) 86 580 5743

lloyd.kuveya@up.ac.za