The Centre for Human Rights on 21 April 2015 launched a report deploring the state of freedom of expression, specifically, and the rule of law, more broadly, in Eritrea.

This report, entitled ‘The erosion of the rule of law in Eritrea: Silencing freedom of expression”, was prepared by students from the UN mandated University of Peace, in Costa Rica, and students and staff of the Centre for Human Rights. (The report is available open-access on the web site of PULP, web site link.)

It was launched in collaboration, and under the mandate of the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and Access to information in Africa of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Commission).

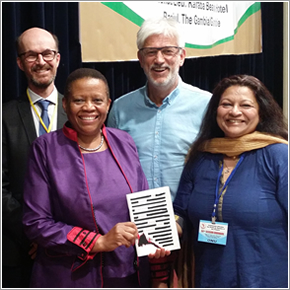

During the launch, which took place immediately following the Opening of the 56th ordinary session of the African Commission, in Banjul, The Gambia, a panel discussed the situation of human rights, and freedom expression specifically, in Eritrea. The panel consisted of: the African Commission’s Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression Advocate Pansy Tlakula; the UN Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Eritrea; an Björn Tunbäck, from Reporters without Borders. The Director of the Centre, Frans Viljoen, chaired the panel.

During the discussion, it was highlighted that the disregard for freedom of expression affects many other rights of Eritreans. It was recalled that, in 2001, in a “Crackdown” to stifle the first signs of simmering discontent, the Eritrean government arrested its serving Minister of Foreign Affairs, 10 other minsters and high ranking officials, and 18 journalists.

Since then, the Commission has taken numerous measures to ensure their release. Responding to communications arising from the Crackdown, the Commission in 2003 found Eritrea in violation of the Charter, in respect of the 11 politicians, and recommended that the detainees be freed. It issued a similar finding and recommendation in 2007, in respect of the 18 journalists. It adopted resolutions in 2009 and 2011, expressing regret at the state’s non-compliance and again urged the state to comply. The Special Rapporteur Adv Tlakula also recalled that the Commission, through her mandate, has directed three urgent appeals to the government of Eritrea.

Today, fourteen years later, their fate remains unknown. Some may have died; those still living have been held incommunicado, most likely in containers in the desert.

The Director of the Centre remarked that Eritrea is unique in Africa, in its apparent ambition to be Africa’s most persistent and continuous violator of its own people’s most basic rights. The Centre for Human Rights therefore called on the Commission to urge the AU political organs to exert concerted pressure on Eritrea to comply. As it seems that the legal processes are not yielding any results, it is now time to involve the political organs of the AU. In line with its approach to the explicit non-compliance by Botswana with the its decision in the Good case, the Commission should, in its next activity report, urge the AU Assembly to take appropriate measures, as allowed for under article 23(2) of the AU Constitutive Act, to exert further political pressure on Eritrea to comply with the Commission’s numerous decisions and resolutions pertaining to these detainees.

Article 23(2) of the AU Constitutive Act reads as follows: “Any Member State that fails to comply with the decisions and policies of the Union may be subjected to … sanctions … and other measures of a political and economic nature to be determined by the Assembly.”