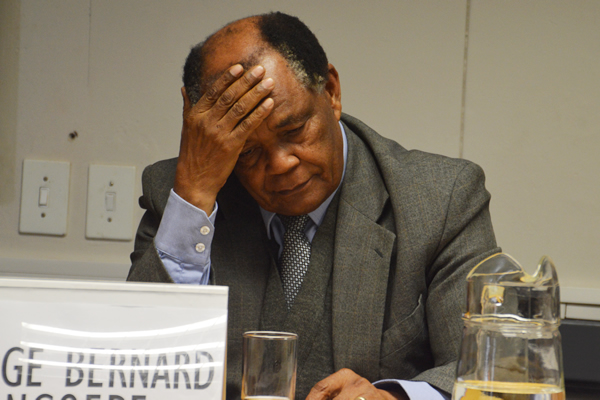

Justice Bernard Ngoepe, the first and as yet only South African to have served as a Judge on the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Human Rights Court), recently lamented the lack of knowledge, awareness and interest among South African lawyers, and the public more generally, of this Court. The African Human Rights Court, which is the principal judicial organ of the African Union, this year commemorates 10 years’ existence. Judge Ngoepe made his remarks at an event hosted by the Centre for Human Rights, University of Pretoria, on 4 August 2016, during which a panel reflected on the accomplishments and challenges of the Court’s first decade.

While the 10-year milestone in the operation of the African Human Rights Court is being celebrated in 2016, the legal instrument establishing the Court (a Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights) was adopted in 1998, and became effective in 2004. The Court, which is based in Arusha, Tanzania, deals with cases of human rights violations in Africa. So far, 30 states have accepted the Court’s jurisdiction. Under the 1998 Court Protocol, states may also accept direct access to the Court by aggrieved individuals in that particular state. To date, eight states have made such a declaration (although Rwanda has recently withdrawn its declaration).

While South Africa ratified the Court Protocol in 2002, thereby accepting the Court’s jurisdiction, it had not made a declaration to allow individuals direct access to the Court. This means that individuals in South Africa first have to approach the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (which makes non-binding recommendations). A case against South Africa can only ever reach the Court if the Commission decides to refer the case to the Court.

In its first decade, the African Court had decided five cases on the merits:

- In Mtikila v Tanzania, the Court decided that a law compelling party membership to run for elective office violated the African Charter.

- In Zongo v Burkina Faso, the Court decided that the state had violated the African Charter by not diligently investigating the murder of an investigative journalist.

- In Konaté v Burkina Faso, the Court found that a term of imprisonment for defaming a politician was excessive, and violated the African Charter.

- In Thomas v Tanzania and Onyango v Tanzania, the Court found fair trial violations.

As part of his intervention, Judge Ngoepe gave some insights into the Court’s jurisprudence. Judge Ngoepe highlighted the value of minority judgments, for example, in the Konaté case, in which the minority expressed the view that any law allowing for criminal defamation would violate the African Charter.

Dr Gina Bekker (Ulster University, Northern Ireland), noted the general marginalisation of the African human rights system in academic literature as well as neglect of its jurisprudence by other regional human rights institutions. Nonetheless, she pointed to the fact that the African system and the Court in particular have the potential to make a significant contribution to international human rights law. In this regard, a number of challenges were highlighted: the challenge of overcoming the post-colonial state’s attachment to sovereignty; the challenge of overcoming the inherent limitations on individual access to the Court and the need to reconceptualise human rights in Africa through the development of an African human rights jurisprudence. In relation to the latter, the imperative for judicial dialogue and cross pollination of judicial decisions with national courts was underscored.

Prof Wessel le Roux (University of the Western Cape) looked at the Court’s relationship with South Africa. He pointed out that, despite the aspiration of our Constitution to establish a transnational or “cosmopolitan” democracy, South Africa has engaged only minimally with the regional and UN human rights systems, with the Prince (ACHPR)and the Prince(HRC)case one of the few exceptions of actual engagement. He pointed out that 1986, when the African Charter entered into force, also marked the demise of “grand apartheid” in South Africa. However, while the African human rights system has experienced positive growth, South Africa’s international relations have not always reflected human rights principles. The promise of “cosmopolitanism” has first been stalled, and is now increasingly being reversed.

Prof Le Roux further argued that the Court has, in response to the minimal engagement by states such as South Africa, taken a number of important non-judicial initiatives. These include: sensitisation campaigns to ensure greater direct access to the Court; and the elaboration of predictable processes of referral to the Court. The Court has also increasingly expressed its vision of becoming an integral part in the project of African integration, a move that would see the increased constitutionalisation of international law in Africa.

Video