- Details

By Ivy Gikonyo

In recent weeks, public attention in both Ghana and Kenya has been captured by disturbing allegations of a foreign national secretly recording intimate encounters with women and circulating those videos online. What might have been private, fleeting moments between consenting adults were transformed into viral spectacles without the knowledge or permission of the women involved.

Before anything else, it is important to draw a clear moral line. Choosing to spend time with someone, even in an intimate setting, does not cancel out one’s rights. Adults are allowed to make personal decisions (wise or unwise). None of those choices amount to consenting to be filmed in secret. None of them translate into permission to have one’s image and vulnerability distributed to strangers across messaging apps and social media feeds.

- Details

By Tendai Mbanje

Citizens of Burkina Faso now endure life stripped of dignity, denied the rights to political participation, association, expression, and assembly. Under the self‑proclaimed pan‑Africanist Captain Ibrahim Traoré, the promise of liberation has curdled into repression. Once hailed as a defender of sovereignty, Traoré has become an oppressor to his own people, extinguishing freedoms and ruling through fear.

- Details

By Michael Aboneka

Ugandans went to polls on 15 January 2026 and despite assurances by the Ministry of ICT and the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC) that the internet would remain on, the government once again pulled the "kill switch" on 13 January 2026 with no legal justifications whatsoever. UCC in their communication noted that they received direction from the national security council to switch off the internet due to security reasons. Despite having It is clear that the 2026 shutdown was not just a political tactic; it was a systemic dismantling of the human rights that underpin a free society.

- Details

UN reports that more than 300 incidents of government-enforced shutdowns have been recorded in over 54 countries in just the past two years

In the 21st century, democracy is meant to thrive on transparency, participation, and the free flow of information. Yet, a new cancer is eating away at its foundations: state-sponsored internet shutdowns. Once considered rare and extreme, these digital blackouts have become disturbingly routine. UNESCO reports that more than 300 incidents of government-enforced shutdowns have been recorded in over 54 countries in just the past two years. The year 2024 was the worst on record since monitoring began in 2016, and the trend has only worsened into 2026.

- Details

By Lakshita Kanhiya, LLD Candidate, Centre for Human Rights, University of Pretoria

A silence that is becoming harder to justify

For a country that frequently presents itself as a model democracy and a defender of the rule of law, Mauritius’ prolonged silence before Africa’s principal human rights body is increasingly difficult to explain. The State’s periodic report under the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (and relevant protocols) has been due since 2024. While Mauritius prepared and submitted its 11th Periodic Report under the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights covering the period from August 2020 to April 2024, it failed to appear before the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Commission / Commission), the treaty body mandated to supervise the implementation of the provisions of the Charter to present it and engage in constructive dialogue with the Commission, so that the Commission can provide its feedback through issuing concluding observations. Mauritius was listed on the agenda of both the 81st Ordinary Session held in November 2024 and the 85th Ordinary Session held in October 2025 in The Gambia. On both occasions, the State delegation did not show up. As 2026 begins, the question can no longer be postponed, is Mauritius ready to account for its human rights record to the African Commission, or will it once again remain absent?

- Details

Uganda goes to the polls on 15 January 2026. Ugandans will elect the president, members of parliament for a five‑year term. As the date of the elections draws near, various stakeholders have argued that these polls are not a celebration of democracy, but rather a repetition of authoritarian consolidation. Despite the presence of 27 political parties and over 21 million registered voters, human rights groups have reported that the electoral environment is marred by violence, repression, and systematic human rights violations. For instance, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have documented widespread intimidation, arbitrary arrests, and torture of opposition supporters, underscoring that these elections mean little for ordinary citizens. What should be a moment of democratic renewal has instead become another occasion for authoritarian entrenchment, echoing the failures seen in Tanzania’s recent elections, yet another troubling example within the East African Community (EAC).

- Details

By Belinda Matore, an LLD candidate and project officer at the Centre for Human Rights, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria

It is indisputable that the modern influencer stands as a central figure in contemporary digital life. These individuals, whether operating on TikTok, YouTube or Instagram, possess the ability to translate complex ideas into accessible stories, set cultural rhythms and command the attention of audiences who often hold a deep scepticism toward traditional institutions. We routinely measure their success by the breadth of their reach, their follower counts, their engagement rates, and their capacity to drive consumer behaviour. Yet by focusing solely on the extent of their influence, we overlook a far more critical question: who influences the influencer? The answer is not merely academic; it is profoundly relevant to the health of public discourse. The systemic forces shaping a creator’s message are, by extension, the forces shaping what millions of people see, share, believe and often fight about online. If we seek to educate the public about online harms and cultivate a more peaceful digital environment, we must first understand and, at times, strategically disrupt these powerful underlying forces.

- Details

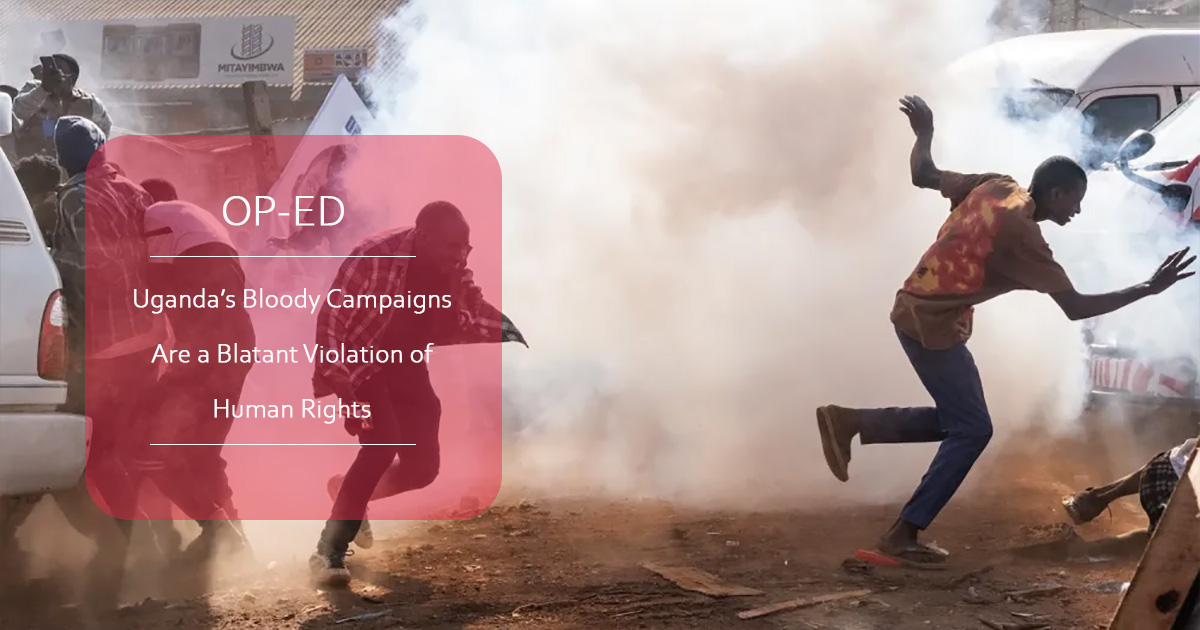

Uganda goes to the polls on 15 December 2025 and the presidential campaigns by the 8 candidates are in high gear. When the campaigns kicked off at the end of September 2025, they were dubbed peaceful and everyone thought, for the first time, that the campaigns will be a peaceful event, free from state orchestrated violence. Lo and behold, we celebrated too early, the campaigns are now bloody with 45 days left to the polling day. This is not the first time the state apparatus has meted violence on Ugandan voters. In November 2020, 54 Ugandans were killed in just two days while exercising their right to protest following the arrest of the opposition candidate, Robert Kyagulanyi. Police and other security agencies fired live ammunitions which led to their death and injured many others. Today, Uganda’s political landscape continues to be stained by the reckless and violent suppression of opposition campaigns especially the brutal dispersal of rallies organized by NUP’s presidential Candidate Robert Kyagulanyi and other opposition candidates in a few instances. What should be moments of democratic participation, public debate, and political choice have instead become scenes of horror with civilians running from gunfire, bodies lying in blood in streets, families mourning loved ones shot down for daring to attend a campaign, imagine, a mere campaign rally.

- Details

By Belinda Matore, an LLD candidate and project officer at the Centre for Human Rights in the Faculty of Law at the University of Pretoria

Imagine a child lacing up their shoes, ready to run onto the field not just to play, but to chase dreams, sometimes their own, sometimes their parents. For many kids, sport is a source of freedom, laughter and discovery. But too often, that joy gets tangled up in adult expectations and ambitions, turning something meant to inspire into a pressure cooker. While parents play a vital role in supporting young athletes, their hopes and desires can clash with a child’s right to choose, enjoy and grow through sport. This tension raises important questions about whose dreams are really being pursued and how we can protect children’s rights to have a voice in the game.

- Details

By Belinda Matore, an LLD candidate and project officer at the Centre for Human Rights in the Faculty of Law at the University of Pretoria

Images of children participating in sport are widespread across social media, club websites, newsletters and broadcasts. While such images celebrate achievement and community, they also expose minors to risks such as exploitation, cyberbullying, identity theft and digital permanence. In South Africa, legal protection for children’s images arises from the Constitution, common law personality rights and the Protection of Personal Information Act 4 of 2013 (POPIA). Yet these frameworks only partially address how children’s images intersect with safeguarding in digital environments.