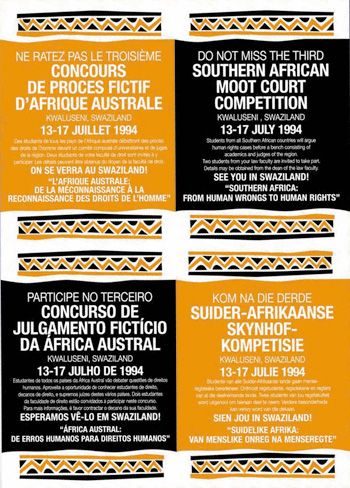

Third African Human Rights Moot Court Competition

Kwaluseni, Swaziland, 13 – 17 July 1994

On 13 to 17 July 1994 the Third African Human Rights Moot Court Competition took place at the University of Swaziland in Kwaluseni, Swaziland. This competition, the third competition of its sort, was again an exciting, but more importantly, a worthwhile event, contributing signifi - cantly towards the popularisation and publicising of human rights issues in Africa.

Twenty-seven universities from the region participated in the event, with a total of around 200 students and lecturers attending the proceedings. The preliminary rounds of the competition were judged by the deans (or their representatives) from the participating universities, while the fi nal round was judged by fi ve chief justices (or their representatives) from some of the participating countries. The judges who participated in the competition this year were Judge Ntabgoba (Uganda), Judge Smith (Zimbabwe), Judge Victorino (Mozambique), Judge Pillay (Mauritius) and Professor Oji Umozurike, previous chairperson of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

The problems for the competition this year dealt primarily with three issues: • refugee rights, • environmental protection and • the rights of women.

The competition was as usual fi erce and the calibre of participants very high. The eventual winners of the competition were the team from the University of Natal, with the University of Cape Town a close second. The winning team will, as their prize, attend a course on the international protection of human rights in Strasbourg, France in September 1995.

An introduction to this year’s competition was the presentation of a lecture series on the international protection of human rights for the benefi t of those participating in and attending the competition. Lectures were presented by a number of experts on the international and regional protection of human rights, from the United Nations, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the European Commission on Human Rights. The lectures presented during the series will be included in the book on the competition, to be published early next year.

At the annual meeting of the extended steering committee held at the competition it was decided that the competition, which mostly gathered universities from Southern Africa, should be expanded to all African law faculties.

We are greatly indebted to our sponsors, whose generous contributions made the staging of this event possible. All sponsors were formally mentioned and thanked in the opening address and in the programme and book on the competition.

Hypothetical Case

It is the year 1995. The Southern African Convention of Human Rights has set up a Southern African Court of Human Rights. The jurisdiction of the court extends to all cases concerning the interpretation and application of part I of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the Charter). Cases can be brought before the court by either a state party to the Convention or after petition to it by the Southern African Commission on Human Rights. Any person or nongovernmental organisation or group of individuals claiming to be the victim of a violation by one of the states party to the Convention on the rights set forth in the charter may petition the Commission. The court may in the case of matters referred to it by the Commission only deal with the matter after all domestic remedies have been exhausted. The Convention further stipulates that in interpreting the Charter, the court must have regard to public international law involving the rights contained in the charter. States Alfa, Beta, Delta Agraria and Zeta are all parties to the Convention and have as such accepted the compulsory jurisdiction of the court. The following two cases have been referred to the court by the Commission:

PROBLEM 1

1. Maria Manase is 17 years old. She used to live with her parents in a remote village in the state Alfa. Her parents arranged a marriage for her to the son of her father’s best friend. Before she could marry him, however, her family and fi ancé insisted that she be circumcised, as is the customary practice in her village. Circumcision in Maria’s case would involve the removal of her clitoris and the labia minora. The ritual would be performed by the elderly women of the village without anaesthetic, after which Maria would be immobilised for a number of weeks while the wound heals. Despite numerous requests by the Alfa Women’s League the government has consistently refused to outlaw the circumcision of women, arguing that it forms an integral part of the cultural identity of villages throughout Alfa.

2. Maria refused to undergo the circumcision ritual. When she told his to her father, he beat her. He explained to her that his people had practiced the ritual since the beginning of time and that an uncut woman was considered polluted, unclean and unmarriageable. Her refusal to undergo the procedure would be considered a disrespectful challenge to the religion and mores of the village and bring him and the rest of the family into disrepute.

3. In spite of all this, Maria did not want to be circumcised for a number of reasons. She felt that the practice was degrading to her womanhood and she recognised the physical danger circumcision could put her in. Her best friend had died three days after having been circumcised.

4. When Maria persisted in her refusal, her father became extremely angry and threatened to kill her to save the honour of the family. The same night, Maria and a group of friends, who all faced circumcision, fl ed the village. While hiding out in he mountains, they received a letter from Maria’ s mother warning them that the men of the village were preparing to set out on a search and that their lives might be in danger.

5. On receiving this news, the group of girls decided to fl ee across the borders into neighbouring Beta. Maria knew that Beta was a member of the United Nations and had signed and ratifi ed the 1951 Convention relating to the status of refugees and its 1967 Protocol, as well as the 1969 Convention on Refugee Problems in Africa. She was also aware that Beta had signed and ratifi ed all of the major conventions dealing wit the rights of children and women. She hoped that Beta would provide them with refuge.

6. Shortly after Maria and her friends had entered Beta, however, they were arrested by the border patrol. Maria immediately informed the commanding offi ce of their fears and made a request for asylum as refugees. The patrol, however, took her and her friends to a camp close to the border where a large number of people who had fl ed the drought and civil was raging in Zeta were accommodated.

7. Maria and her friends were separated and with the camp already overcrowded, placed in tents with other refugees. Adult males predominantly occupied the tent Maria was assigned to. Being one of the only few females in the tent, Maria ended up cleaning the tent and fetching water, wood and food from the collection point each day.

8. A month later, Maria was informed that due to the constant infl ux of people from Zeta, the refugee tribunals could not handle all the cases and that their case, being of relatively little importance, could not be considered by the refugee tribunals. As a result, Maria and her friends were to be deported to their country of origin as soon as possible, as were a large group of people living with them in the camp.

9. At this point, the refugee Crisis Committee (RCC), a non-governmental organisation working with refugees, became aware of Maria’s plight and assisted Maria in bringing an urgent application against the government of Beta for an order restricting it from returning Maria to her village in Alfa and compelling it to move Maria and her friends from the camp to accommodation in a home for children. The government of Beta opposed the application. The application was turned down. Maria thereafter petitioned to the Commission, who in turn referred the case to the Southern African Court of Human Rights.

PROBLEM 2

1. Agraria, with a total human population of 3.2 million, is one of the smaller independent states of southern Africa. The population is made up of a number of tribal kingdoms, one of which, Accasia, is situated in a remote but beautiful valley in rural Agraria. The Accasians make up nearly 60 000 of the total Agrarian population. The majority of the Agrarian population, however, lives in the city of Libertyville, where conditions are overcrowded. The rural areas generally suffer from erosion and a lack of irrigation.

2. In stark contract with the rest of Agrarian countryside, the Accasians’ fertile valley is lushly overgrown with a variety of beautiful plants. The valley has been the home of he tribe for the past 300 years. The Accasians regard the whole valley as sacred land, but attach special importance to the upper valley where all their ancestral graves are situated.

3. The valley and the Accasian people living there entered into the global spotlight a few years ago when it was discovered that the valley forms the natural habitat for the Pulp plant, a fern not found anywhere else in Agraria and only in two other spots in the world. Every effort to grow the plant outside the valley has failed.

4. When questioned about the plant, the tribesmen told researchers that the gods came down to earth to hand their ancestors the only seed of the plant with the instruction to cultivate and protect it. In return, the gods promised to give them a fertile valley that would provide the tribe abundantly with fruits and vegetables. For this reason, the plant is considered to be holy and it is used extensively in all the religious and healing rituals of the tribe.

5. After the discovery of the Pulp plant, the government of Agraria, who had signed and ratifi ed the 1972 Convention for the protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage earlier, had the valley listed in terms of the convention as a World Heritage Site. The plant was also included in the Annex to the 1968 African Convention or the Conservation of Nature to which Agraria is a party.

6. Continued research into the valley, however, established that the area is rich in orex, a rare and strategically important mineral. After extensive prospecting, the Government of Agraria applied to the Mining Development Board, an administrative body set up in terms of the Agrarian Mining Act of 1993, to have the Accasian valley declared a Designated Mining Area. Section 2 of the Mining Act stipulates as follows:

Decisions by the Board in terms of the Act are taken after consideration of all relevant factors relating to the issue in question

7. During the Board hearing it became clear that the mining operation would endanger the lives of the Accasians living in the valley and that the whole tribe would have to be relocated in a neighbouring valley. Evidence presented at the hearing by Agrarian Heritage Crisis Committee (AHCC) indicated that such a move would effectively mean the end of the Accasian people and their cultural and religious heritage. It was also stated that even without their relocation, the mining of the forests and ancestral graves would have the same effect. The Accasian people were afforded the opportunity to make a written presentation, but their request to present overall evidence before the Board and to be legally represented was turned down because the Mining At did not provide for such measures.

8. The Board eventually decided to allow extensive open-air mining operations in the valley. The most important sites approved for mines included the upper valley and most of the larger Pulp forests. When later requested for reasons of the decision, the Board refused to give any, stating bluntly that the Mining Act does not require the giving of reasons for administrative reasons.

9. In support of the proposed mining operations, the Minister of mining announced that the export of orex will lead to an increase of almost three times Agraria’s present external revenue. He further announced that the increase will be used to undertake a hospital building scheme in urban areas and an irrigation canal in the rural areas. These announcements were made in the form of a press release and were reported by the main newspaper, the Agrarian Mail.

10. The Accasians, however, appealed against the decision of the board, arguing that they were not afforded a proper hearing and that, in any case, the decision of the Board should be set aside as it violated fundamental rights in terms of the Southern African Convention on Human Rights. The government of Agraria opposed the appeal, which was subsequently turned down by the High Court of Agraria.

11. After petition to it by the AHCC, the Commission referred the case to the Southern African Court of Human Rights, who has now set down in matter for hearing.