Eighth African Human Rights Moot Court Competition

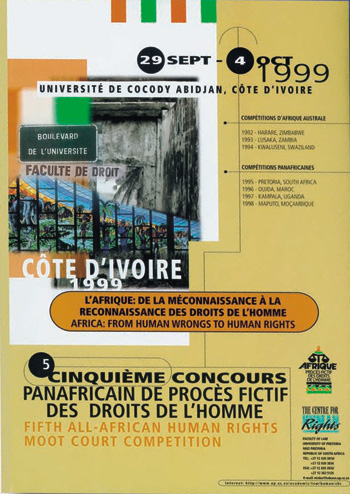

Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 29 September – 4 October 1999

The Eighth African Human Rights Moot Court Competition was held at Université de Cocody, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, from 29 September to 4 October 1999. For the fi rst time in its eightyear history, the Moot brought together students and lecturers from 59 law faculties representing 33 African countries, being half of all the law faculties in Africa. Each of the 59 faculties that participated was represented by two students and a faculty representative. The event lasted 6 days and was an enriching and rewarding intellectual and social exercise for everyone involved.

Over the years, most of the participating law faculties have developed a system of internal moot courts at the faculty level to determine the students who would represent the faculty at the All-African Human Rights Moot Court Competition. When they arrived in Abidjan, most of the students were therefore already very familiar with their arguments which had the effect of raising the standards of the competition quite signifi cantly.

All participants were lodged at the Golf Hotel Inter-Continental on the Boulevard Lagunaire in Riviera II, a quiet Abidjan neighbourhood.

The morning of 29 September was taken up by team registration which consisted in handing in personal details and memorials to the organisers and receiving in return a conference bag, T-shirt and sundry documentation. The opening ceremony was held in the Ceremonial Hall at Cocody Town Hall, an honour bestowed on the Moot as the building had not been offi cially opened yet. The hostess was Madame Kondé, the Deputy Mayor of Cocody, who welcomed all participants to Côte d’Ivoire and applauded them for taking part in this singularly important event. Speeches were also delivered by the following people: Prof. Asseypo Hauhouot, President of Université de Cocody; Prof. Ouraga Obou, Dean of the host Faculty of Law; Prof. Christof Heyns, Director of the Centre for Human Rights, and the President of the Supreme Court of Côte d’Ivoire who offi cially opened the event. The speeches were punctuated by a musical performance with a human rights theme by a group called Sakholo that performed traditional musicals around contemporary African problems. Immediately afterwards, there was a cocktail reception in the courtyard of the Town Hall.

The competition in the Moot takes the form of preliminary rounds in which the faculty representatives are constituted into benches of between 5 and 7 judges each and assigned to specific “courtrooms”. The teams of two students each then argue the case four times over the next 2 days, twice for the Applicant and twice for the Respondent against 4 different teams and in 4 different courtrooms, but never before a bench which has their faculty representative sitting on it. The students are evaluated on their oral performance including their ability to answer questions from the judges, as well as on their pre-submitted written arguments.

The preliminary rounds were therefore held on Thursday 30 September and Saturday 2 October on the premises of the Faculty of Law. The preliminary rounds are conducted in the 2 offi cial languages of the competition: English and French, each team of students arguing in a separate court in its fi rst language. On Friday 1 October, the one-day training course on “The International Protection of Human Rights” which is compulsory for all participating students, was presented at the Faculty of Law. In total 11 lectures were delivered: 5 in English and 6 in French.

English

- General Introduction to the International Protection of Human Rights Prof. Christof Heyns, Director, Centre for Human Rights, University of Pretoria, South Africa

- The UN system of Human Rights Protection Prof. Christof Heyns, Director, Centre for Human Rights, University of Pretoria, South Africa

- The African System of Human Rights Protection Prof. Frans Viljoen, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, South Africa

- The European System of Human Rights Protection Mr. Wolfgang Strasser, Deputy to the Registrar of the European Court of Human Rights, Strasbourg, France

- The Inter-American System of Human Rights Protection Mr. David Padilla, Assistant Executive Secretary, Inter-American Human Commission of Human Rights, Washington DC, USA Français

- Introduction générale à la protection internationale des droits de l’homme Professeur Meledje Djedjro, Faculté de Droit, Université de Cocody, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire

- Le système onusien de protection des droits de l’homme Mr Mathieu Bile, Faculté de Droit, Université de Cocody Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire

- Le système africain de protection des droits de l’homme Prof. Degni Segui, Faculté de Droit, Université de Cocody Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire

- Le système européen de protection des droits de l’homme Mr. Wolfgang Strasser, Adjoint au Greffi er, Cour européenne des droits de l’homme

- Le système inter-américain de protection des droits de l’homme Prof. Hubert Houlaye, Faculté de Droit, Université de Cocody Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire

- Punir les crimes de guerre: mécanismes de répression nationaux et internationaux Ms Isabelle Daoust, Coordinatrice Services consultatifs, Comité International de la Croix-Rouge Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire

On Sunday 3 October, the moot court excursion took the participants to Grand Bassam, the fi rst capital of Côte d’Ivoire. They had a good time shopping at the art and craft market, having lunch in a seaside restaurant and going for a swim or just relaxing on the beach afterwards.

The fi nal round was held on Monday 4 October in a singular location, namely the auditorium of the African Development Bank in Plateau – Abidjan’s Central Business District, courtesy of the President of the Bank through the Head of the Legal Division Mr Francis Ssekandi. With very good equipment and excellent translators doing simultaneous interpretation, the fi nal was for the Moot Court as a whole the cherry on the top of the pie. The fi nal round opposed the best four teams from the preliminary rounds, 2 from the English rounds and 2 from the French rounds. They were then newly reconstituted into two teams of four students each: one anglophone and one francophone team on each side. By draw of lots, they chose which side of the case they will argue.

They were:

Applicant:

- Université de la Réunion and the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

Respondent:

- Université de Cocody, Abidjan and the University of Nairobi

The 7 judges who sat on the bench in the fi nal round, presided by the President of the Constitutional Court of Côte d’Ivoire, put the fi nalists through a diffi cult but immensely challenging set of questions as the latter battled to fi nish their oral arguments. The finalists are evaluated exclusively on their oral arguments in this phase of the competition.

The judges in the fi nal round were:

- Mr Noël Nemin, President, Constitutional Court of Côte d’Ivoire

- Mr Justice Albie Sachs,Judge, Constitutional Court of South Africa

- Prof. E.V.O. Dankwa, Member, African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

- Mr David Padilla, Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

- Mr Emile Yakpo, General Secretary, African Society of International & Comparative Law, London

- Mr David Strasser, Deputy to the Registrar, European Court of Human Rights

- Ms Nanaré Damienne, Dean of Law, Université de Bangui, Central African Republic

The combined team for the Respondent won the fi nal round. The three best oralists from the three separate language groups in the preliminary rounds were:

English:

- Steven Budlender, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

French:

- Jérôme Gruchet, Université de la Réunion

Portuguese:

- Manuel Castiano, Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, Maputo, Mozambique

The closing dinner and prize-giving ceremony were held on the lagoon front at the Golf Hotel. The President of the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire, HE Henri Konan Bédié, was represented by the Minister of Higher Education, himself a Professor of Law and former Dean of the host law faculty. He expressed the good wishes of the President and congratulated the organisers on their vision and initiative, and the participants on their industry and commitment to the establishment of a culture of human rights in Africa.

The great satisfaction expressed by participants at the overall success of the Moot Court was unprecedented. The positive comments received by the organisers came from all the different groups represented – students and lecturers as well as the different language and regional groups. One comment that was consistently repeated by many of the faculty representatives who attend the moot court annually was that the level of the competition was very high and has been increasing steadily every year.

As usual, for many of the students it is the fi rst time that they travel abroad and compete in an event of such magnitude. This truly oncein- a-life time opportunity to meet so many other young people from all across Africa on a human rights plane is a moving experience that leaves many of the young people committed to chanelling their energy and time towards fostering a human rights culture in their country. The one-day course on “The International Protection of Human Rights” that is a fundamental element of the week’s proceedings, is for many of the students the fi rst formal human rights instruction they have received.

The organisers would like to continue with the African Law Students’ Internship Programme which offers some students who participated in the Moot Court the opportunity of doing a three-week practical internship at a law fi rm or human rights organisation in another African country. Since 1995, 21 students have been placed in organisations all across Africa. These internships have proved to be of tremendous personal benefi t to the students in exposing the different legal systems of other African countries to them and allowing them the opportunity of making a positive contribution to the work of the host organisation. The Secretariat of the OAU has expressed the desire to take in four students for internships.

The Fifth All-African Human Rights Moot Court Competition was a great success. In Abidjan, the organisers achieved one major goal which they had been working towards for a number of years: attracting the participation of half of all the law faculties in Africa. It is an immense logistical operation which was realised this year, but at the same time maintaining high competition standards and a quality of service that makes the event memorable. It is important to note that of the 59 faculties present, 17 were French-speaking. Over the years, the number of French-speaking faculties has increased steadily. The Moot has succeeded in sensitising many of these faculties about the importance of participating in such an event. The task was always more diffi cult because mooting is not a common feature of legal education at university level in Francophone Africa. It is important to secure the continued participation of these faculties and our current goal as organisers is two-fold: to increase the total number of participating faculties to 80, with half of them being French-speaking.

The multiplying effects of the Moot Court continue to be felt. Student and lecturer exchange programmes are facilitated, external supervision and research is made possible, and the general need for human rights awareness that is absent in many parts of Africa is slowly being addressed. The Moot Court continues to attract publicity both in the host country and across the continent. In the light of the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights setting up the African Court of Human Rights, there is no doubt that the Moot Court is making its contribution towards the creation of an indigenous African human rights jurisprudence.

As the millennium turns and human rights in Africa is no longer debate but a condition sine qua non for sustainable human development, it is clear that the All-African Human Rights Moot Court Competition has become the single most important rendezvous for the youngest and the brightest African law students; and that is has earned a place among the great meetings that are charting a course for Africa, as part of the greater community of nations, into the twenty-fi rst century.

Hypothetical Case

1. It is the year 2001. Assume that the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights establishing an African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the “African Court”) has entered into force on 30 March 2000, and that the African Court has been set up.

2. The State of Armazia is a member of the Organisation of African Unity (the “OAU”), and has ratifi ed the following African human rights instruments:

- The 1969 OAU Convention Relating to the Specifi c Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa (ratifi ed on 20 September 1980)

- The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the “African Charter”) (ratifi ed on 10 March 1987)

- The Protocol to the African Charter Establishing an African Court (ratifi ed on 1 February 2000). Armazia has also made a declaration in terms of article 34(6) of this Protocol at the time of ratifi cation.

Since 1963 Armazia has also been a member state of the United Nations (“UN”) and has ratifi ed the following international human rights treaties of the UN:

- The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”), (ratifi ed on 12 June 1979) but not any of the Optional Protocols thereto

- The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (“ICESCR”) (ratifi ed on 12 June 1979)

- The Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (of 1951), as well as the 1967 Protocol thereto (ratifi ed on 14 March 1982).

3. Armazia is a country in the north of Africa. Its only neighbouring state is Batanga, also a member state of the OAU and UN. Each of these countries is rich in oil deposits, which are exploited by multinational corporations in which the government has a 51% share. Armazia is a developing country. In the 1999/2000 budget, the government spent 10 per cent on education; 7 per cent on health care services and 5 per cent on housing. Due to a dramatic drop in crude oil prices the government’s total budget for 2000/2001 was reduced by 10 per cent. Due to a strict structural re-adjustment plan, worked out between the government and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) the government was forced to cut spending in numerous areas, including a 12 per cent cut to the health budget, a 14% cut to the education budget and a 13 per cent cut to the housing budget. This led to a drastic increase in school fees. Many schools were forced to turn away pupils who could not pay the admission fees. Twenty per cent of the budget was set aside for defence representing an increase of 7 per cent on the previous year’s budget. About half of this amount was earmarked for the building of a nuclear submarine harbour, and the acquisition of four nuclear submarines. In her budget speech, the Minister of Finance motivated this allocation with reference to “the vulnerability of Armazia in the Mediterranean basin”. A special allocation of $2 billion (3% of the national budget) was also made for the erection of a statue of the Armazia head of state, president Abubu. In her speech, the Minister motivated this allocation by stating that it would “symbolise and enhance national unity”.

After constitutional amendments in 1990, Armazia has become a multi-party democracy, with a Constitution entrenching a justiciable Bill of Rights. The following are excerpts from the Bill of Rights:

Article 7:

Fundamental rights and liberties are recognised and their exercise is guaranteed to citizens under the conditions and forms provided by law.

Article 8:

Armazians of both sexes have the same rights and the same duties. They are equal before the law without distinction of race, origin or religion.

Article 9:

Every human person is inviolable, and has the right to respect of their life, moral and physical integrity, or personal identity and the protection of the intimacy of their private and family life.

Article 10:

Each citizen has the right to the free development of his person, with respect to the rights of others, good morals and public order.

Article 11:

No citizen may be submitted to degrading or humiliating treatment or to torture.

Article 12:

No one may be arrested, indicted, or detained except in cases provided for by law promulgated prior to the infraction which it prohibits. Arbitrary arrests and detention are forbidden.

Article 13:

Every accused is presumed innocent until the establishment of their culpability through a regular process which offers guarantees indispensable to his defence.

Article 14:

Punishment is personal. No individual may be held responsible and prosecuted in any fashion for an act not committed by him or her.

Article 15:

Customary and traditional practices on collective responsibility are prohibited.

Article 18:

Every citizen has the right to freely circulate through the interior of the national territory, to leave it and to re-enter it. These rights may only be modifi ed in cases provided by law.

Article 25:

The Armazian citizen travelling or residing abroad benefi ts from the protection of the State within the limits fi xed by the law of the host country and international accords to which Armazia is a party.

Article 26:

The State of Armazia accords the right of asylum, upon its territory, to foreign nationals under conditions determined by law. No foreign national may be extradited for a crime of opinion.

Article 28:

Defence of the fatherland is a sacred duty of every Armazian.

The following are excerpts from other parts of the Constitution, representing “principles of national policy”:

Article 40:

The State shall actively promote, respect and protect the welfare and development of the people of Armazia by progressively adopting and implementing policies and legislation aimed at achieving the following goals -

(a) Gender equality

To obtain gender equality for women with men through -

(i) full participation of women in all spheres of Armazian society on the basis of equality of women with men;

(ii) the implementation of the principles of non-discrimination and such other measures as may be required; and

(iii) the implementation of policies to address social issues such as domestic violence, security of the person, lack of maternity benefi ts, economic exploitation and rights to property.

(b) Nutrition

To achieve adequate nutrition for all in order to promote good health and self-suffi ciency.

(c) Health

To provide adequate health care, commensurate with the health needs of Armazian society and international standards of health care.

(…)

(h) Children

To encourage and promote conditions conducive to the full development of healthy, productive and responsible members of society. (...)

(k) International relations

To govern in accordance with the law of nations and the rule of law and actively support the further development thereof in regional and international affairs.

Article 41:

The principles of national policy contained in this Chapter shall be directory in nature but courts shall be entitled to have regard to them in interpreting and applying any of the provisions of this Constitution or of any law or in determining the validity of decisions of the executive and in the interpretation of the provisions of this Constitution.

Article 115:

Peace treaties, treaties of commerce, treaties or accords relating to international organisations, those concerning State fi nances, those making provision for cession, exchange or joining of territory, shall only be approved or ratifi ed according to the law.

They only take effect after approval or ratifi cation. No cession, exchange or joining of territory shall be valid without the consent of the people.

Article 116:

Treaties or agreements regularly approved or ratifi ed shall have, from their publication, an authority superior to that of laws, under the reservation for each treaty or agreement of application by the other party.

4. Batanga is made up of two ethnic groups, the Zoli and the Yawa. The government is controlled by the majority group, the Zoli. The Yawa minority (making up about 15% of the total population) lives in the mountainous south, and is mostly involved in agriculture. Early in 1999 the Yawa started a campaign of civil disobedience, because they felt that the region in which they lived was under-developed. When their leaders considered this to be unsuccessful, the Yawa Liberation Movement (“YALMO”) started on a campaign of violence, bombing selected government installations in the south of the country. The government responded by banning YALMO, and by arresting a number of Yawa males over the age of 16 years. The leadership of YALMO, in particular the leader himself, Mavindile X, went underground, and launched sporadic attacks on members of the Batanga security forces deployed in the area. Mavindile X chose to disappear from public view, because he was clearly recognisable due to the fact that he wore an eye-patch on his left eye.

5. At this stage the relations between Armazia and Batanga were strained. Soon after the fi rst arrests, 6000 male members of YALMO illegally crossed the border to Armazia. Soon after their arrival, they applied for refugee status in Armazia. The Armazian Minister of the Interior issued a declaration granting the YALMO members refugee status in terms of s 2(2) of the Armazia Refugee Act. Section 2 of this Act reads as follows:

- Subject to the provisions of this section, a person shall be recognised as a refugee for the purposes of this Act if - a) owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reason of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country, or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his or her former habitual residence is unable or owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it; b) owing to external aggression, occupation, foreign domination or events seriously disturbing or disrupting public order in either part or the whole of his or her country of origin or nationality, is compelled to leave his or her place of habitual residence in order to seek refuge in another place outside his or her country of origin or nationality; or (c) he or she is a member of a group or category of persons declared to be refugees in terms of subsection (2).

- Subject to the provisions of subsection (3), the Minister may, if he or she considers that any group or category of persons are refugees as defi ned in paragraph (a) or (b) of subsection (1), declare such group or category of persons to be refugees either unconditionally or subject to such conditions as the Minister may impose: Provided that such a group shall, until the contrary is proved, be presumed to be refugees in accordance with subparagraphs (a) and (b).

- The Minister may revoke any declaration made in terms of subsection (2) by notice in the Gazette.

6. Later in 1999 the Batangese government succeeded in suppressing the YALMO campaign. Peace returned to Batanga. An election was held, in terms of which the Yawa people was granted 5% representation in the national Parliament. A new head of state was also elected. The relations between the two neighbouring states improved. A factor which continued to complicate relations was the presence of the 6000 refugees in Armazia. They continued with activities demanding greater representation of Yawa people in the Batanga government. They formed the YALMO-in-exile (YALMOX) movement and they printed pamphlets which were smuggled into Batanga. They also founded a radio station in Armazia which transmitted broadcasts into Batanga.

7. During discussions between the heads of State of Armazia and Batanga, it was agreed that the 6000 “refugees” should be returned to their country of origin. Without making any announcement, the Armazian authorities started rounding up members of YALMOX. This “rounding up” consisted of these members being arrested and detained in a holding centre. After a while, these events were made public. The head of state announced that all members of YALMOX will be “repatriated”. He also invited all members, who had not been detained in the holding centre, to voluntarily surrender themselves. He stated that the others will be kept in detention there until the remaining members (whose names appear on documentation held by the Armazian government) would “give themselves up”. The reason for this move was stated to be because the YALMOX members were “compromising the security of a neighbouring OAU member state”. Soon thereafter the names of these 6000 people were published in the Government Gazette, stating that the refugee status granted to them had been revoked.

8. While waiting for all 6000 former refugees to assemble, the Armazi immigration authorities found that a number of the detained YALMOX members had been found guilty of criminal conduct while in Armazia, and decided to repatriate them before the others. One of the crimes committed by two of these men was that of “unnatural sexual relations”, contrary to Section 19 of the Armazi Criminal Code. This section reads as follows: “It is an offence for any male person to commit an unnatural act of a sexual nature with any other male person”. The two men were convicted after they had engaged in consensual sexual intercourse. The immigration authorities started making preparations to send these two men back to Batanga immediately.

9. The people in the holding centre had been denied legal representation since their detention. When some of them asked to see lawyers, they were asked if they had money to pay for legal representation. None of them had any substantial funding, and on this basis the request was denied.

10. The conditions in the holding centre were as follows: The detained persons slept on mattresses on the grass; in big military tents. As the rainy season had already started, and the tents were pitched in low-lying terrain, the tent fl oors and mattresses became drenched and soggy. At night swamp insects called Armazia prawns, emerged from their holes in the ground to pester inmates. After about two weeks, six men had symptoms of pneumonia (coughing and fever). They requested the offi cials in charge that they be examined by a medical practitioner, or that they be hospitalised. After consideration of the request they were informed that there was no money available in the budget of the Department of Immigration for such treatment. However, fi rst aid service was available, staffed by a nurse. Some very basic fi rst aid medication was available, such as aspirin, bandages and cough medicine. The whole group was assembled and informed that only basic medical treatment was unfortunately available, but that they may, at their own expense, be examined by the medical practitioners of their choice. None of the men detained made use of this offer.

11. One of the detainees escaped and approached a human rights NGO, Human Rights for All in Armazia (“HURAIA”). An urgent application was fi led in the High Court of Armazia, in which the following were claimed:

- The denial of legal representation is contrary to the Armazia Constitution;

- Section 19 of the Armazia Criminal Code is unconstitutional and therefore the immediate expulsion of the two men convicted of this offence is contrary to Armazia’s international law obligations.

- The intended mass expulsion of the detainees is in confl ict with Armazia’s international law obligations.

- The budgetary allocation is in confl ict with Armazia’s constitutional and international law obligations.

12. The High Court refused the application. Leave to appeal to the Supreme Court, the highest court in Armazia, was refused. In terms of the Judicature Act, an appeal from a High Court may be instituted only if the judge or judges deciding the High Court case fi nd that there is a reasonable prospect that the High Court decision will be overturned on appeal.

13. The applicants now approach the African Court directly in accordance with Article 6(5) of the Protocol, on the following basis:

- The denial of their right to legal representation is a violation of the African Charter.

- Section 19 of the Armazi Criminal Code is in confl ict with the African Charter.

- The intended mass expulsion of the refugees is a violation of the 1969 OAU Convention and of the African Charter.

- The Armazi budget is in confl ict with that state’s obligations under the African Charter and other international law obligations.

14. Prepare arguments for the Applicant (HURAIA) and the Respondent (the government of Armazia), on the basis of the alleged violations of Armazia’s obligations under the African Charter.