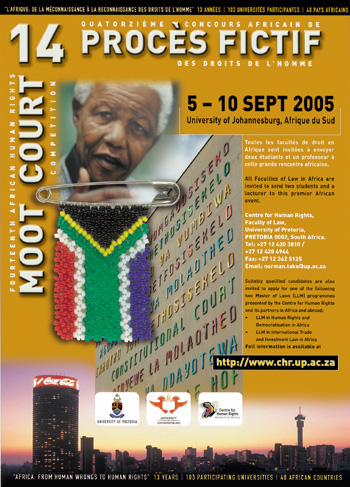

Fourteenth African Human Rights Moot Court Competition

Johannesburg, South Africa, 5 – 10 September 2005

The Fourteenth African Human Rights Moot Court Competition, which is organised by the Centre for Human Rights at the University of Pretoria in collaboration with the Faculty of Law at the University of Johannesburg, was held from 5 to 10 September. Over 60 universities from across the continent registered to participate this year.

The Moot Court brings together law students, academics, judges and human rights experts from all over Africa to argue and debate a hypothetical human rights case in a mock courtroom. Each university is represented by 2 students and the human rights lecturer. Separate preliminary rounds are held in English and French. The best two teams from each language group then advance to the fi nal round where, by draw of lots, they merge to form two new combined teams of four students each: two English-speaking and two French-speaking students on each side. The judges in the fi nal round are international human rights lawyers of the highest standing, and simultaneous interpretation is provided. The newly-appointed Chief Justice of South Africa, Mr Justice Pius Langa presided at the fi nal round.

From its modest beginnings in 1992, the Moot Court has, over the years, become a major event on the African human rights calendar. It provides a singularly rich experience for everyone involved. The students get the chance to formulate proper legal arguments for both sides in the hypothetical case before a bench comprising law lecturers. This year’s Moot is given special signifi cance by the fact that the protocol for establishing such a court for Africa, entered into force earlier this year, and the process to appoint judges and make this court a reality is currently underway.

As part of the training provided through the Moot Competition, this year, a one-day conference on human rights in Africa was held on Friday, 9 September. Conference papers dealt with contemporary human rights issues of relevance to Africa, including those raised in the hypothetical case to be argued in Johannesburg this year (mercenaries, child soldiers, and unconstitutional changes of government).

The opening ceremony took place on Monday 5 September 2005 at the University of Johannesburg’s Auckland Park Campus. The Deputy Minister of Education, Mr Enver Surty, delivered the keynote address.

The highlight of the programme was the fi nal round when the four best teams participated at the Constitutional Court on September 10. The University of Cape Town and the Université de Cocody, Côte d’Ivoire, appeared for the Applicant against the American University of Cairo and Université Mohammed Ier, Morocco, who appeared for the Respondent. The Applicants were declared the winners.

Mrs Julia Joiner, Commissioner for Political Affairs at the African Union, who was one of the judges, delivered the keynote address at the Closing Ceremony which followed the fi nal round.

The results of the 14th African Human Rights moot Court Competition:

Finalists - Applicants:

Anglophone

- University of Cape Town, South Africa (Mr Nicholas David Friedman, Mr Andrew Sekandi)

Francophone

- Université de Cocody, Côte d’Ivoire (Mr Yao Armand Tanoh, Mr Lassana Koné)

Finalists - Respondents:

Anglophone

- American University of Cairo, Egypt (Ms Suzanne Shams, Mr Tabe Kevin Mbeh)

Francophone

- Université Mohammed Ier, Morocco (Ms Majdouline Ben Saad, Ms Nour El Houda Qortobi)

Overall winners

- Applicants (University of Cape Town, South Africa and Université de Cocody, Côte d’Ivoire)

Runners up

- Respondents (American University of Cairo, Egypt and Université Mohammed Ier, Morocco)

Hypothetical Case

1. It is September 2005. The African Court of Human and Peoples’ Rights (the Court) has been established with its seat in Johannesburg, South Africa. The Rules of Procedure of the Court, adopted by the judges, determine that when a case has been submitted under article 34(6) of the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Establishment of an African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the Court Protocol), the Court should deal with both the admissibility and the merits of the case without involving the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the African Commission) if at all possible.

2. The small African State of Salama gained its independence from the United Kingdom in 1965. Salama is a member of the United Nations (UN) and the African Union (AU) (and previously, of the Organisation of African Unity (the OAU)). (It ratifi ed the Constitutive Act of the African Union in December 2000.) The Constitution of Salama has a Bill of Rights that was included at the insistence of the British as part of the independence Constitution. The Bill of Rights contains rights similar to those enshrined in the original European Convention on Human Rights, before the adoption of any of the protocols thereto. According to the Salamaan Constitution (section 103), the Vice-President is to become President if the President dies. Presidential elections should then, according to the Constitution, be held within six months. Only then may the Supreme Court inaugurate the new President. The Supreme Court is the highest judicial organ in the country, with the competence to give fi nal decisions in all matters. There are also three High Courts. Their jurisdiction includes constitutional matters. In addition, there are numerous lower courts. Lower courts do not have the competence to deal with any matter arising from the Bill of Rights. Although the Constitution of Salama further provides for a multi-party system, the country has been ruled by the same party since independence. The elections that have taken place since independence up to 1975 have been described as “farcical” by independent observers, due to very low voter registration and turn-out.

3. In 1975, the then Minister of Defence, Roger Akono, took over power by successfully conspiring with some members of the armed forces to assassinate President Fall, the “Father of the Nation”. Roger Akono issued an executive decree that installed him as President for life, and was inaugurated by the Supreme Court. The previously serving Vice-President fl ed the country during the turmoil.

4. Salama has ratifi ed the four 1949 Geneva Conventions (but not the additional Protocols) (in 1970), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (in 1973) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (in 1997). Salama has signed but not ratifi ed the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed confl ict (in 2003). Salama has further ratifi ed the Convention for Elimination of Mercenarism in Africa (in 1988), the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Charter) and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (on 31 January 2004). After ratifying the African Charter in 1990, it was incorporated into its national legislation by the African Charter (Incorporation) Act 1991. Salama ratifi ed the Court Protocol in January 2000, with a declaration in terms of article 34(6) thereof. It did not sign or ratify any other relevant human rights instruments.

5. Salama has since its independence, but increasingly after the inauguration of President Roger Akono, been singled out by the international community as one of the worst oppressors of human rights in the region. In 1980, an opposition movement (Salamas Against Oppression (SAO)) was formed, with an agenda to oust the repressive government of President Roger Akono “by peaceful means and persuasion” (as its Manifesto reads). SAO was led by General Mujere, a high-ranking army offi cer who had been dismissed from the Salama National Defence Force in 1979, on charges of insubordination. Dissatisfi ed with the rate of progress in Salama and the unlikelihood of free and fair elections, General Mujere transformed SAO into a guerilla movement. Since the early 1980s, SAO has been engaged in small-scale attacks on military installations and personnel in an attempt to overthrow the government. The confl ict escalated, and civilians became the main casualty.

6. In its 1989 Annual report on Salama, Amnesty International (AI) stated that General Mujere has, according to numerous interviewees who were members of the guerilla forces, recruited boys as young as 15 years to join his forces. The boys helped General Mujere to infi ltrate President Roger Akono’s forces, in order to supply him with intelligence, but they did not participate in attacks on the “enemy”. Some of these boys were successful in their attempts at infi ltration. On 20 November 2003, when General Mujere’s camp was attacked by government forces, a signifi cant number of General Mujere’s soldiers were killed. The General himself was saved by two boy soldiers who managed to bring him to safety by taking the guns of their fallen comrades and killing many of President Roger Akono’s soldiers. It is alleged that the boys were 16 years old, but they had no birth certifi cates and they were killed in a later attack undertaken by the government forces. The boys who infi ltrated ex-President Akono’s forces to help General Mujere were subsequently conscripted into the Salama National Defence Force.

7. On 1 May 2004, as President Roger Akono returned to his country from a state visit to the Far East, he was killed when his plane was shot down. It is unclear who shot down the plane. Fearing for his life, the Vice-President, Mr Nayoko, went underground.

8. General Mujere managed to use the power vacuum left by President Roger Akono’s death and Mr Nayoko’s disappearance to take power in a coup d’état on 20 May 2004. In order to strengthen his overstretched troops, later in May 2004 he recruited 200 mercenaries from a neighbouring country (Zanazo) to assist him in the fi ght against forces loyal to deceased President Roger Akono. He also received weapons and logistical support from Zanazo, which argued at a subsequent AU Assembly meeting that with General Mujere in power the humanitarian situation in Salama would improve and the endless stream of Salamaan refugees to Zanazo would end. The mercenaries left Salama on 1 June 2004, after having assisted General Mujere in defeating an unsuccessful counter coup led by Mr Nayoko. After the defeat, also on 1 June 2004, Mr Nayoko fl ed to another neighbouring state, Abadar. On 2 June 2004 the Salama Parliament declared General Mujere President of Salama, in the light of the fact that section 103 of the Constitution could not be complied with, due to Mr Nayoko leaving the country. When President Mujere took over, the composition of the armed forces remained intact.

9. Abadar and other African countries protested against the coup d’état. Despite the urgings of Zanazo to the contrary, the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the African Union at its session in July 2004 condemned the unconstitutional change of government. Since President Mujere refused to step down from power, and no elections were held, the Assembly imposed a variety of sanctions on Salama, acting under article 23(2) of the Constitutive Act and the membership of Salama in the Africa Union was suspended.

10. Under the new government, a Commission to Reveal the Atrocities of the Past (CRAP) was set up. The Commission, in its interim fi ndings after a few months of investigation, concluded that the government of President Roger Akono had been very corrupt. The new government under President Mujere managed to get control over and to repatriate the foreign bank accounts of former President Roger Akono. The money thus obtained was being used to implement social programmes, including free medical services and free compulsory education until the age of 14. These programmes had not existed under the previous government.

11. Despite these reforms General Mujere’s coup d’état met signifi cant opposition also within Salama, especially in the capital Mara. Yasmina Ekambi was the president of the Students’ Representative Council at the University of Mara. Shortly after the coup of 20 May 2004, Ms Ekambi organised a protest at the university against General Mujere. She obtained permission according to the legally prescribed mechanisms to hold “a peaceful protest meeting that will not undermine the security of the public”. Some of the participants in the demonstration (which took place on 21 June 2004) destroyed university property and attacked university staff and students, especially those known to support General Mujere. One person, a known supporter of General Mujere, was killed under unclear circumstances. When she realised that proceedings were getting out of hand, Ms Ekambi used a megaphone to call on the protesters to refrain from any further violence. At that point, the security forces arrived at the scene and broke up the demonstration using “minimal force” (according to a subsequent government press release). Several students were arrested, including Ms Ekambi.

12. Ms Ekambi was taken to Nido prison. The prison was privatised during the rule of President Roger Akono, in the late 1990s, under pressure from the IMF and World Bank to effect structural reforms. As there was no other prison in Salama, and the owners of Nido prison (Private Prisons Ltd, or “PP Ltd”) in order to save money had closed down the section for women, she was placed in a cell with male prisoners. On the night of her arrival, she was raped repeatedly by some of the other prisoners. After she complained to a PP Ltd staff member the next day, Ms Ekambi was placed in a smaller cell, with older men. Although there was no legislative framework in place to ensure that certain minimum standards were adhered to in privatized entities previously owned by the state, an offi cial from the Department of Prisons inspected the prison on a weekly basis and reported to the Minister. Actions (such as the dismissal of staff) resulting from these visits had so far been taken on two occasions, following recommendations by the Department’s inspector. No action was taken with regard to the rape of Ms Ekambi, as “no offi cial complaints have been received by the Department of Prisons” (according to a government spokesperson).

13. Ms Ekambi was charged with conspiracy to commit murder, an offence for which the maximum sentence is life imprisonment. She approached a well-known criminal law expert, Mr Kwame Bembe, with a request to defend her and to assist her with claiming damages for the treatment in prison. However, Mr Bembe refused to take her case when she informed him that she did not have money to pay him. Except in cases where the death penalty may be imposed, there is no legal aid in Salama.

14. Ms Ekambi was sentenced to life imprisonment in August 2004 after a one-hour trial before a Special Court constituted under the Constitution (consisting of a high-ranking offi cer of the National Defence Force, one judge of the High Court and a senior lawyer nominated by the Minister of Justice for that purpose). The Special Tribunal is a permanent constitutional body. The Minister of Justice, on advice of the head of the prosecuting services may “assign any case involving threats to public order or state security” (under section 88 of the Salamaan Constitution) to the Special Tribunal. In September 2004 Ms Ekambi was transferred to the newly reopened wing for female prisoners at Nido prison. The opening of this new wing was made possible by foreign donor funding, as many western donor countries were positive about the new government’s social reforms and tough stance on corruption.

15. In January 2005 Ms Ekambi managed to smuggle out a note that reached her mother. She contacted the local press and the story was soon spread around the world. A staff member of RAPPORT, an international NGO based in London, read in Le Monde about the judgment passed on Ms Ekambi. (RAPPORT enjoys observer status with the African Commission and sometimes some of its members attend the Commission’s sessions.) Through its contacts in Salama, RAPPORT tried in vain to appeal the judgment of the local court, as the period to lodge an appeal against a fi nding of the Special Court, as provided for under Salamaan law (a period of three months) had expired before any appeal had been instituted.

16. After increased international pressure elections were held and a civilian government took over power in March 2005, Ms Ekambiwas released. The AU sanctions against Salama were lifted and its AU membership was restored (in July 2005). Ms Ekambi’s application for compensation, addressed in a letter to the relevant Minister (the Minister of Justice), met with a negative response. In his response to her request, the Director-General of the Department of Justice wrote as follows: “After consultation with the Minister, I wish to state the following in respect to your request for compensation: As much as the current government regrets the incidents that allegedly caused harm to Ms Ekambi, as a new, democratic and non-sexist government we are not responsible for the actions of the former undemocratically elected and unrepresentative regime, that did not embody the will of the people and cannot cause fi nancial harm and hardship to future generations by redirecting resources away from socio-economic needs that are part of the process of reconstruction that is underway.”

17. Ms Ekambi was indigent and did not have any money to pursue the matter further in the Salamaan courts.

18. RAPPORT decided to submit the matter directly to the African Human Rights Court (in terms of article 34(6) of the Court Protocol). RAPPORT asked the Court to determine the following issues:

- Did the unconstitutional change of government in Salama in 2004 violate the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights or any other relevant international law obligation of the state?

- Does the use of mercenaries and child soldiers by General Mujere constitute a violation of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights or any other relevant international law obligation of the state?

- Is the treatment of Ms Ekambi during her time in prison a violation of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and other relevant international law obligations of the state and is the state of Salama obliged to pay her compensation?

- Are the proceedings related to Ms Ekambi’s trial a violation of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and other relevant international law obligations of the state? Deal with the question of admissibility under each issue.