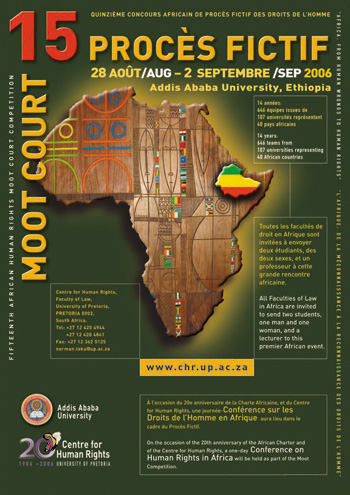

Fifteenth African Human Rights Moot Court Competition

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 28 August – 2 September 2006

During the week of 28 August - 2 September 2006, students and faculty representatives representing 61 law faculties from 29 countries across Africa, assembled in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, for the 15th African Human Rights Moot Court competition which was organised by the Centre for Human Rights of the University of Pretoria and co-hosted by Addis Ababa University.

The competition simulated the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, which is being established by the African Union at the moment for the African continent. The judges for the real court were appointed recently by the African Union and the court should start to function very soon.

The President of Ethiopia, HE Mr Girma Wolde-Giorgis delivered the keynote address at the Opening Ceremony which was held in the historical Africa Hall of the UN Economic Commission for Africa.

The four preliminary rounds were conducted in French and English over two days in the lecture rooms of the Law Faculty of Addis Ababa University, with each team arguing in a separate court in either of the languages before panels of judges comprised of faculty representatives. Each team was required to argue twice for the Applicant and twice for the Respondent.

One day was allocated to relaxation and participants travelled south of Addis Ababa by bus through the green, luxuriant countryside (it was the rainy season in Ethiopia) to the Sodere Hot Spring Resort where they had fun in the sun, and a tasty lunch. The following day, as part of the training provided through the Moot Competition, everyone attended a one-day conference on human rights in Africa. Conference papers dealt with contemporary human rights issues of relevance to Africa, including those raised in the hypothetical case the students had argued this year (HIV/AIDS policy, abortion laws and treatment of women and orphaned children).

The highlight of the week took place in the Plenary Hall of the African Union on Saturday, 2 September, when the top two teams from each language group merged to form two new combined teams of four students each: two English-speaking and two French-speaking students on each side to participate in the fi nal round. The Vice-President of the Federal Supreme Court of Ethiopia presided over a panel of international jurists, which included SA Constitutional Court Judge Yvonne Mokgoro; Justice Rita Makarau, the recently-appointed Judge President of the High Court of Zimbabwe; Ms Julia Joiner, Commissioner for Political Affairs, African Union; Commissioner Bahame Nyanduga of the African Commission; and Mr Said Al Habsy, Chief Legal Counsel of the Africa Practice Group of the World Bank, among others.

The University of Malawi and the American Université du Caire of Egypt appeared for the Applicant against the University of the Witwatersrand and the Gaston Berger University from Senegal for the Respondent. The judges were most impressed at the calibre of the arguments presented and congratulated both teams on their presentations and on they way in which they had acquitted themselves during incisive questioning from the Bench. They commented on how diffi culty it had been to make a selection but in the end the trophy was awarded to the team appearing for the Respondent. Mr Michael Abiodun Thomas from Lagos State University, Nigeria Town was judged the best English-speaking oralist in the preliminary rounds; Mr Darly Aymar Djofang from the Université Dschang, the best French-speaking oralist, while Mr Danilo Mangamela of the Universidade Catolica de Mocambique from Mozambique was awarded the prize for the best Lusophone oralist.

During their summing up the judges were unanimous in their praise for both teams. Justice Yvonne Mokgoro of the South African Constitutional Court said that if she were to die that night, she would die happy, knowing that Africa was in good hands. Zimbabwean Judge Rita Makarau said that if she ever needed a lawyer, she would be sure to engage one of the students whose arguments had so impressed her. Professor Alpha Oumar Konaré, who delivered the passionate keynote address at the Closing Ceremony, thanked the Centre for Human Rights for presenting the competition and for its efforts to establish a new generation of law students committed to bringing peace to Africa. Professor Christof Heyns, Director of the Centre for Human Rights, after thanking everyone involved, commented that the Plenary Hall of the African Union in Addis Ababa was a most appropriate venue, more especially at this critical stage of the African Court’s history.

Download the keynote address by Prof Alpha Oumar Konaré

A fun-fi lled, informal dinner at the Hilton Addis Ababa Hotel where the audience was entertained by some lively traditional Ethiopian dancing, brought the week’s proceedings to a close.

Hypothetical Case

1.It is August 2006. The African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Human Rights Court) has been established. Rule 77 of the Rules of the Court adopted by the judges under article 33 of the Protocol establishing the African Human Rights Court determines as follows: When a matter has been referred to the Court under article 34(6) of the Protocol establishing this Court, the Court may, given its supplementary relationship with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, either (a) deal with the admissibility and merits of the matter without referring it to the African Commission; or (b) refer the matter to the African Commission for its decision on admissibility; or (c) refer the matter to the African Commission for its decision on admissibility and merits.

2.Monia, an African state, independent since 1965, is a member of the United Nations (UN) and the African Union (AU). Monia is classifi ed as a least developed country by the World Bank.

3. The total population of Monia is 25 million. The bulk of the citizenry of Monia rely on agriculture as their livelihood. About 65% of the population live in rural areas, and 35% in cities.

4. Monia is a state party to the African Charter on Peoples’ and Human Rights (African Charter). It ratifi ed the Protocol establishing the African Human Rights Court on 4 March 2003, with a declaration in terms of article 34(6) of the Protocol. Monia also ratifi ed the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of Children on 14 August 2004 and the Protocol to the African Charter on the Rights of Women in Africa (African Women’s Protocol) on 14 February 2006. It is also a state party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which were all ratifi ed in 1996. It has not ratifi ed any other relevant human rights instrument, but signed the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in 1995.

5. Monia functions according to a Constitution providing for a multiparty democracy, with a justiciable Bill of Rights, containing rights very much akin to those enshrined in the European Convention on the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. Apart from the right to education, the Bill of Rights does not contain any justiciable socio-economic rights. The Constitutional Court is the highest domestic court of constitutional jurisdiction. Article 12 of its Constitution declares that international agreements duly ratifi ed by Monia are “part and parcel of the law of the land”. Moreover, such treaties duly ratifi ed by Monia are the “supreme law of the land” by virtue of article 9 of its Constitution. Article 44(1) of the Constitution provides that, when interpreting the Bill of Rights, courts “must take into account relevant international law”.

6. Monia is one of the poorest states in Africa. The World Bank estimated the average annual per capita income in Monia at US$500. Approximately 58% of the population live in conditions defi ned as “extreme poverty” (that is, living on less than US$1 per day). The World Health Organisation (WHO) has noted that investment made by the government of Monia in preventive and primary health services was noted as being low. In particular, the allocation in the annual budget to the health department has been criticized for representing only 3,2% (in the 2003/4 fi scal year), 4,5% (in the 2004/5 fi scal year) and 5,3% (in the 2005/6 fi scal year). This contrasts sharply with allocations for defence, which made up 13%, 11,5% and 12% of the total budget in the corresponding fi scal years. Monia has been involved in a border dispute with a neighbouring state, Nubia, for a number of years. Hostilities have never broken out, and the matter has in 2001 been submitted to the International Court of Justice, whose jurisdiction both states accept. This matter is still pending before the International Court of Justice. During his last three budget speeches, the Minister of Finance motivated the allocation to defence with reference to the “appreciation of the government of risks to peace, public safety and state security”. The increase in health spending in 2004/5 was mainly due to the establishment of a Directorate of HIV/AIDS within the department of health, and the appointment of a respected retired cleric to the newly created position of deputy minister of health, with specifi c responsibility for HIV/ AIDS. In line with the priorities identifi ed by the new deputy minister, posters, billboards and radio messages were used especially in urban areas to disseminate the principle of “ABC” (Abstinence, Be faithful, and Condomise).

7. According to WHO estimates, the maternal mortality rate is 168 per 10,000 mothers giving birth. Every year, some 170,000 women and girls are subjected to female genital mutilation (FGM) in Monia. The Criminal Code of Monia (in article 123) states as follows: Female genital mutilation is prohibited, and any person involved in such a procedure in guilty of an offence, punishable to a fi ne or a maximum of 6 months imprisonment or both.

This provision has rarely been enforced. In 2005, for example, available government data indicate that there were only two prosecutions under article 123, one of which culminated in a conviction. In its 2005-2010 Health Policy of Monia, the government of Monia proposes the collection of the necessary data on health (including the existence of FGM) as a starting point towards evaluating progress of implementation. The Health Policy also points to the National Prosecutor’s stated reluctance to “tear families apart by forcing one family member (especially children) to testify against another family member (a sister or mother), which entails the risk of family break-up”.

8. At present, Monia is experiencing a high prevalence of HIV infection among its inhabitants. The adult infection rate is approximately 18%. The most recent (2004) government-sponsored survey of HIV prevalence in ante-natal clinics across the country shows a prevalence rate among pregnant women of 27% in urban and peri-urban areas and 13% in rural areas, an average increase of 3% from the previous year. In 2004 alone, the WHO estimates that approximately 90,000 infants were infected with HIV through mother-tochild transmission (MTCT).

9. Upon learning about the rise in the prevalence of HIV/AIDS, the government withheld the information to prevent the disclosure of the fi gures in the hope of ensuring the fl ow of tourists to the country, a signifi cant source of dwindling foreign currency to Monia, and to protect its international standing from being tarnished. However, it did not take long for the magnitude of the prevalence to be revealed through the work of civil society organizations and others operating in Monia. The prevalence of HIV infection was also exacerbated by the high rate of domestic violence against women in Monia. A recent newspaper survey, conducted under the supervision of a university sociology lecturer, has revealed that at least one third of married women in Monia have experienced violence from their spouses in the last year. There is no specifi c domestic violence legislation in place in Monia.

10. The prevalence rate of HIV/AIDS also entailed an alarming increase in the number of destitute orphaned children, estimated at 100,000. Many of the children are engaged in remunerative work, such as begging and prostitution, to sustain their lives. A study by an internationally respected Centre for AIDS Research (CAR) at the University of Monia indicates that the children were subject to abuse, neglect, exploitation and violence, and that the majority of the children were also divested of the property belonging to their deceased parents including their houses, in some cases, by their own relatives. A great majority of these children did not have recourse to the governmental organs of Monia seeking protection and restitution of their property, as the 1968 Law on Property provides that “only adults may hold title to immovable property”. A few of the children who made efforts to acquire property rights at the death of their parents were not successful in their efforts. Wide publicity was given to the CAR report in Monia. The deputy minister of health reacted by expressing the government’s concern, and by promising that the “people’s concerns are the government’s concerns”. The deputy minister also pointed to that fact that the government in 2002 appointed a task team to investigate legislative reform to ensure that children are protected against exploitative labour practices, adding that he expected their report to be tabled in Parliament soon.

11. According to the government’s most recent comprehensive health statistics (1999), the rate of condom use is very low, with an estimated 14% of sexually active people ever making use of condoms. The 2005-2010 HIV/AIDS Strategic Plan and Policy Framework advocates the use of condoms, but indicates that one of the main reasons for the low use of condoms is the lack of availability of condoms across the country. In a widely published speech, the Deputy President of Monia expressed the view that condom use is likely to lead to promiscuity. Especially in rural areas, condoms are usually not available, mostly due to perceived resistance from the community. This causes health workers not to promote condom use. Commercially, condoms are available at the cost of the equivalent of 50 US cents (half a USD). The government of Monia contends that international assistance to combat the HIV/AIDS pandemic in Monia has been meager. It is now in the process of applying for the United States Presidential Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) funding.

12. According to Monia’s 2005-2010 HIV/AIDS Strategic Plan and Policy Framework, symptoms of opportunistic infections and HIVassociated diseases (such as cryptococcal meningitis, pneumonia and tuberculosis) are treated for free in state hospitals. This is the case only when one produces a “poverty-based exemption certifi cate” from grassroots administrative organs of the government. Such a certifi cate is issued upon presentation of evidence of one’s HIV positive test and by demonstrating that one cannot afford to pay for the treatment. Residents complain that the process to obtain the “poverty-based exemption certifi cate” is cumbersome and exposes them to stigma in their own vicinity, as they have to declare their HIV status to obtain it.

13. However, even after having secured the exemption, there is no general availability of or access to anti-retroviral (ARV) medication. At four selected sites, ARVs are provided, but only to HIV positive persons who have a CD4 count of below 100. There is only one laboratory that can do these CD4 tests. As a consequence, there are considerable delays in the testing process. Of the approximately 20,000 people tested HIV positive in 2005, only 3,000 had, by the end of 2005, received their CD4 test results. Of these, 1,200 qualifi ed for ARV treatment.

14. Ms Claire Wade heads an NGO, the Monian Women’s Coalition (MOWOCO). In 2005, MOWOCO started a campaign of awareness-raising about the lack of access to condoms, the slow CD4 tests, as well as the lack of access to ARVs such as Nevirapine. The campaign took the form of mass protests by women on the streets of the capital, Moniaville. MOWOCO also espoused the cause of hundreds of thousands of children orphaned due to the loss of their parents to AIDS demanding legislative changes to ensure the expansion of existing meager social services. One type of social grant exists, namely “disability grant”, for which persons qualify who are suffering from a permanent disability that, according to legislation, “signifi cantly impairs that person’s ability to work”. In the only relevant court case so far in Monia, a person’s HIV positive status was not accepted as a “permanent disability” under the relevant legislation. MOWOCO also brought a case on behalf of an indigent HIV positive woman who lost her two-year-old HIV infected son, claiming that her and her son’s constitutional rights were violated due to the unavailability of Nevirapine. In January 2006, the Constitutional Court of Monia, in MOWOCO v Minister of Health of Monia, ruled that there is a constitutional obligation on Monia to render free medical assistance in the form of Nevirapine to prevent MTCT. Failure to do so, the Court ruled, would violate the mother’s and the child’s right to life and to human dignity.

15. One of the spokespersons of MOWOCO is an openly HIV positive woman, Ms. Devine Mawuwa. When she recently learnt that she was pregnant, she approached a government hospital to hear what the likelihood was that the newborn will be infected with HIV. She was informed that the risk of HIV infection is about 33%. Transmission of the virus during pregnancy and during the course of labour and delivery accounts for 65 to 70 percent of infections transmitted from mother to child. However, she was told that the normal course of treatment with Nevirapine, namely a single dose to the mother during delivery and followed by a single dose to the child within 72 hours of birth, can reduce transmissions during pregnancy, labour and delivery by 50 percent. Following the Constitutional Court fi nding in MOWOCO v Minister of Health, the government has negotiated a price reduction of Nevirapine with the pharmaceutical company responsible for its manufacture, resulting in the drug being provided at 25% of the usual retail price. Nevirapine has as a result become available in all urban medical facilities in July 2006, and the deputy minister has announced that the treatment will be “rolled out” to all rural areas by July 2007.

16. After considering all the information, including her own experience of living with HIV in a stigmatized society, she decided to ask the doctor to perform an abortion. The doctor, after carrying out a medical examination, discovered that Ms Mawuwa has been pregnant for eight weeks, and that an abortion could be performed without signifi cant risk to the mother. However, the doctor refused to perform the abortion, as the Criminal Code of Monia (in article 345(1)) states that performing an abortion is a criminal act, and constitutes “infanticide”, which is punishable with life imprisonment to both the mother undergoing and the doctor performing the abortion. However, under article 345(2) of the Criminal Code, an exception is allowed for: An abortion is allowed if in the opinion of two doctors it is “absolutely necessary” to “save the lie of the mother or the foetus or to prevent a danger to the health of the mother” and when the pregnancy is “the result of rape or incest”. Ms Mawuwa was refused an abortion on the ground that her life was not in danger. Ms Mawuwa’s public protest about this mattfer was taken up and made part of MOWOCO’s campaign. MOWOCO approached about 80% of the Members of Parliament (MPs) and engaged them in discussion about the need to more aggressively market and distribute condoms. The response, informed by the conservative religious sentiments of most MPs, was overwhelmingly negative, and focused on the need to “preach” the message of “ABC”.

17. MOWOCO took action against the government of Monia seeking country-wide provision of more accessible ARVs and CD4 tests by approaching the High Court with an application arguing that the current situation constitutes a violation of the Constitution. In particular, counsel argued that the fi nding in MOWOCO v Minister of Health should be extended to deal with these two issues, namely free access to ARVs to all persons in need thereof and free access to CD4 tests for all persons who have tested HIV positive, as well. The High Court ruled that the case cited was distinguishable, as the MOWOCO case dealt principally with the rights of the child. The High Court concluded that there was no violation of the Constitution. On appeal, the Constitutional Court confi rmed the High Court decision.

18. As a result of these events, these issues were covered extensively in local, African and international newspapers and media outlets. You are legal advisor to an international NGO (African Women’s Rights Alliance - AWRA), which has been granted observer status before the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights and is based in Nubia. After learning about these events on TV and in newspaper reports, and consulting with Ms Wade, AWRA in August 2006 submits a communication to the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights on behalf of the women who are effectively denied access to condoms, medical treatment, and abortion in Monia, and on behalf of “all children in Monia who have been orphaned due to the loss of their parents to AIDS”.

19. Prepare arguments to the African Human Rights Court, for both the applicant and the respondent, on the following issues:

- Should the Court deal with the matter in terms of Rule 77(a)?

- Does the law of Monia relating to abortion constitute a violation of the African Charter or any relevant international law obligation of the state?

- Does the lack of access to condoms constitute a violation of the African Charter or any other international law obligation of the state?

- Does the lack of ARV treatment and CD4 tests constitute a violation of the African Charter or any other relevant international law obligation of the state?

- Does the treatment of orphaned children by the government of Monia constitute a violation of the African Charter on Peoples’ and Human Rights or any other international law obligation of the state? Deal with the issue of admissibility under each of the issues, if relevant.