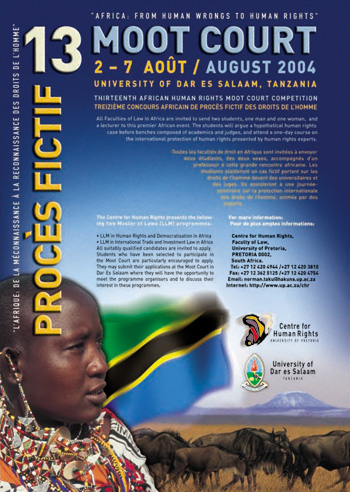

Thirteenth African Human Rights Moot Court Competition

Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, 4 – 9 August 2004

The Thirteenth African Human Rights Moot Court Competition was held at the University of Dar es Salaam from 2 to 7 August 2004. The Moot brought together students and lecturers from 58 law faculties representing 22 African countries. Each faculty was represented by two students and a lecturer.

After registration in the morning of 2 August, the opening ceremony was held at the Golden Tulip Hotel in Dar es Salaam and was formally opened by Ms Hilda Gondwe, Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Community Development, Women and Children, Tanzania. Speeches were also delivered by the Dean of the Faculty of Law of the University of Dar es Salaam and Prof Christof Heyns, Director of the Centre for Human Rights.

The competition itself takes the form of preliminary rounds in which the faculty representatives are constituted into benches of between 3 and 5 judges each and assigned to specifi c “courtrooms”. The teams of two students each then argue the case four times over the next 2 days, twice for the Applicant and twice for the Respondent. The students are evaluated on their oral performance including their ability to answer questions from the judges, as well as on their pre-submitted written arguments.

The preliminary rounds were held on Tuesday 3 and Thursday 5 August at the University of Dar es Salaam. The preliminary rounds are conducted in the 3 offi cial languages of the competition: English, French and Portuguese, each team of students arguing in a separate court in its fi rst language.

On Wednesday 4 August, the one-day training course on “The International Protection of Human Rights” which is compulsory for all participating students, was presented.

Meanwhile, in a nearby hall, African lecturers and scholars were in a SUR (a collection of Latin American academic institutions that collaborate on initiatives to advance awareness and action for human rights protection) meeting. They reviewed SUR’s recent publications and discussed human rights priorities for Africa and legal strategies that SUR could adopt to help achieve them. Professor Christof Heyns, Director of the Centre for Human Rights, opened the programme before turning the fl oor over to Jeremy Sarkin, Professor at the University of the Western Cape in South Africa, and Daniela Ikawa, an Assistant Professor from the Catholic University of Sao Paulo in Brazil and SUR Programme Coordinator. These dedicated human rights advocates were aided by Abeeda Bhamjee, a Refugee Legal Counsellor from the University of Witwatersrand’s Law Clinic in South Africa, and Sufi an Bakurura, a Law Professor from the University of Kwazulu- Natal in South Africa.

On Friday 6 August, the moot court excursion took the participants on a ferry trip to Zanzibar where they went on a guided tour in Stone Town, visited a spice fi eld and had lunch in a resort along the Indian Ocean.

The fi nal round was held on Saturday 7 August at the University of Dar es Salaam. The fi nal round opposed the best four teams from the preliminary rounds, 2 from the English rounds and 2 from the French rounds. They were then newly reconstituted into two teams of four students each: one anglophone and one francophone team on each side. By draw of lots, they chose which side of the case they will argue. They were:

Applicant:

- Université Abomey Calavi (Bénin) and University of Pretoria (South Africa)

Respondent:

- Université Marien Ngouabi (Congo) and the University of Nairobi (Kenya)

The finalists are evaluated exclusively on their oral arguments in this phase of the competition.

The judges were:

- Prof Brian Burdekin, Visiting Professor, Raoul Wallenberg Institute, Sweden

- Prof EVO Dankwa, Faculty of Law, University of Ghana and Member of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights; Former Chairperson, African Commission

- Justice Akua Kuenyehia, Judge and Vice President of the International Criminal Court, The Hague

- Ambassador Salamata Sawadogo, Chairperson, African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights

- Mr Abdulqawi A. Yusuf, Director, Offi ce of International Standards & Legal Affairs, UNESCO, Paris

- Dr David Padilla, American Fullbright Professor.

The competition was won by the combined team for the Applicant.

The closing dinner and prize-giving ceremony were held at the Tanzanian Parliament building in Dar es Salaam. All the judges congratulated the students for their high academic level and the organisers for their hard work.

The Thirteenth African Human Rights Moot Court Competition was a successful event. Of the 58 faculties present, 10 were Frenchspeaking and 2 Lusophone. It is expected that there will be 70 faculties present at the Foutheenth African Human Rights Moot Court Competition, with at least one third of them being French-speaking.

After thirteen years, the Moot Court has developed a life of its own. It is the biggest meeting of young African lawyers around the theme of human rights. It is also the only event in Africa, outside the meeting of University Rectors and Principals, to bring together so many African universities. The students who arrive at the Moot have been selected form a pool of students who took part in a selection process. This means that many students, at law faculties across Africa get to study the hypothetical case and master the African Charter.

The Moot Court was covered by the media both in Dar es Salaam and South Africa. A lot of research is done by the students to prepare their arguments and comments from judges in the preliminary rounds indicate that the standards are very high.

The Moot Court competition has established itself as an outstanding vehicle for teaching human rights in Africa and is a regular feature on the calendar of law faculties in Africa. With over 1200 past participants and approximately 6,000 others who have researched and argued the hypothetical cases over the years, the Moot Competition is by far the most important and far-reaching medium for teaching human rights in Africa.

The Fourteenth African Human Rights Moot Court Competition will be held at the University of Johannesburg from 2 to 7 July 2005.

Hypothetical Case

1. It is August 2004. The African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Human Rights Court) has been established with its seat at Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. One of the Rules of Court, Rule 81, adopted by the judges, determines as follows:

When a matter has been referred to the Court under article 34(6) of the Protocol establishing this Court, the Court may, given its supplementary relationship with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, (a) deal with the admissibility and merits of the matter without referring the matter to the Commission; (b) refer the matter to the Commission for its decision on admissibility; or (c) refer the matter to the Commission for its decision on admissibility and merits.

2. Kibunia, an African country, is a member of the United Nations (UN), the African Union (AU) and the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and is classifi ed as a developing country by the World Bank. Kibunia is also a member of the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) and a state party to the Paris Convention of 1883 as amended up to 2003. It obtained its independence from France in 1962. In 1995, when its fi rst multi-party elections took place, the party of Alphonse A Wawe, the Kibunia People’s Democratic Movement (KPDM), won an easy victory. This party has remained in power since then.

3. The population of Kibunia is approximately 7 million, made up predominantly of members of the Edo ethnic group. Kibunia is a very fertile country, making small-scale agriculture a favoured activity of many of its citizens

4. Kibunia ratifi ed the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Charter) in 1985, the Protocol thereto establishing the African Human Rights Court on 2 March 2003 (with a declaration in terms of article 34(6) thereof), and the Protocol to the Charter on the Rights of Women in Africa (African Women’s Protocol) on 16 August 2003. Kibunia has also ratifi ed the AU Convention on Prevention and Combating Corruption in 2003. It is a state party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Conven3 tion on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), all ratifi ed in 1996. It is not a state party to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) or the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT). As a member of the UN General Assembly, Kibunia campaigned for and voted for the UN Declaration on the Right to Development of 1986.

5. Kibunia functions according to a multi-party Constitution, with a justiciable Bill of Rights. The Bill of Rights contains rights similar to those enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Constitutional Court is the highest domestic court of constitutional jurisdiction. In terms of the Constitution (article 272), international law, duly ratifi ed by the state, forms part of national law and enjoys a status superior to “domestic law”. Kibunia also has a Patent Law Act, which provides that a compulsory licence may be issued where a product is not being supplied to the domestic market on reasonable terms.

6. Odo Yed is a Kibunian citizen, living in a rural part of the country. When she reached marriageable age in 1993, her family entered into negotiations for her marriage. After the required bride wealth (three cows) was paid to her family, she departed to live in the communal area of her husband’s tribe. When she arrived, Odo insisted that her husband, Bobo Mabunda, build them a separate home some distance away from that of his father and brother, who also lived in the communal area. This Bobo did, and also built an enclosure for his own cattle, then numbering 10. To the couple, a girl, named Caroline, was born, after a year of married life. After two years, another girl, Nicole, was born. During this time, Bobo’s job was to supervise the care for his and his father’s cattle. Odo looked after the children and the house. After the death of their father in 2000, Bobo’s older brother, Sama, for all practical purposes stepped into their father’s shoes. The relationship between Bobo’s family and that of his brother remained cordial, but not warm.

7. Early in 2001, a drought hit the countryside. Rumours also reached the village that foreign investment in the capital city, Buniaville, was opening up numerous employment possibilities. In search of fortune, Bobo went to Buniaville, where he got a job working in a factory. After this, he went home monthly, taking some money for the household each time. Over time, his visits became less and less frequent. Later in 2001, Odo realized that she was again pregnant. After Bobo had received this news, his visits ceased. Over this period, Odo had taken over the role of looking after the family’s cattle, which had grown to about 25 in number.

8. On 30 June 2002, about a month before the birth was due, Odo went to a government health centre in the nearby town of Beauville. She consented to an HIV test, which revealed that she was HIV positive. She was told that her baby was likely to be born HIV positive as well. There was, however, a government mother-to-child-prevention (MTCP) scheme in terms of which this could be prevented. This consisted of a dose of Nevirapine to the mother before the birth, and to the child after birth. Nevirapine has been patented under the Kibunian Patent Law Act. According to offi cial government policy, Nevirapine or other medication necessary to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV was to be provided free, and made available to all pregnant mothers without charge. This policy was, however, not applied universally and different hospitals and health centres applied different rules. At the Beauville government health centre, the nurse who dealt with Odo required that Odo pay her the equivalent of $20 for this medication. Odo was shocked, and did not know what to do because she did not have that amount of money. She immediately wrote to Bobo, explaining the situation, but did not receive a response.

9. A baby boy was born, but from the start he was quite weak and fragile, and died before he had reached the age of one year. Throughout this time, Odo tried to establish the whereabouts of Bobo. Eventually, after the death of the boy early in 2003, she went to look for him herself and found out that Bobo had died about six months before. No one could clearly explain the cause of death, but she found out that he had lost weight, and had had severe bouts of pneumonia. She obtained a copy of his death certifi cate, which stated that he had died “of natural causes”.

10. On her return, she presented this to Bobo’s brother, Sama, claiming that she was now the owner of the house built by Bobo and their cattle. She explained that she wanted to leave, and would sell the cattle to have enough money to settle elsewhere. She was also feeling ill, and wanted to pay for a good doctor. After consulting the tribal elders, Sama explained that in terms of the customs and traditions of the Edo tribe, only male heirs are recognised. If Bobo had left any male children, they would have inherited his estate. Since he had not, the next heir is his brother, Sama himself. He explained that she would retain the right to stay in the house, but that she had no claim to the cattle. He would also always be “there for her”, as required by their customs.

11. Soon thereafter, Sama married a second wife. He sent his fi rst wife and three children to live in the house occupied by Odo and her children. After developing more symptoms of weight loss and fatigue, Odo went to the same health centre where she had received her HIV diagnosis. There she was told that there was “nothing that could be done”, as the state does not have the capacity to manufacture these drugs and has to import them at astronomical prices. The drugs are, therefore, not provided by the state. She was told not to work too hard, and to eat nutritiously.

12. At this time, the impact of HIV-AIDS was becoming very visible in Kibunia. According to the only reliable data, an annual prevalence survey of pregnant mothers, the incidence had risen from 6% in 2001 to 11,5% in 2002. In 2002/3, the government increased its health budget by 5%, bringing it up to 4,5% of the total annual budget. In numerous statements, the Minister of Health indicated that the main strategy of the government to combat AIDS is through education and “moral regeneration”. Television and radio programmes, billboards and pamphlets warned against HIV and AIDS as a “killer”, and programmes were launched encouraging abstention from sex outside and before marriage. The government also adopted, as part of its Criminal Code, the offence of “wilful infection of another with HIV, knowing that one is HIV positive”, an offence for which life imprisonment could be imposed upon conviction. The only other specifi c measure adopted by the government was the prohibition of discrimination in the public service against employees who are known to be HIV positive.

13. After Odo had returned home, her health deteriorated rapidly. She died on 16 November 2003. Her older daughter, Caroline, now nine years old, was very upset. She did not attend the funeral, but ran away from the house and family, to Beauville, ending up at one of the two institutions in Beauville for “children in distress”. When the social worker there conducted an interview and established the facts, she told Caroline that she did not meet the requirements – she still had a family, and had to return. She was accompanied home.

14. Caroline immediately left home again – this time she went to Buniaville, the capital city, where she met members of the non-governmental organization, Kibunians for Justice (KIJU), an NGO enjoying observer status with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. The legal offi cer of KIJU, Prudence Patel, organised temporary refuge for Caroline and decided to take the matter to court. She listened to Caroline’s story, and decided to investigate some of the allegations. Three pregnant women, working with KIJU, accordingly went to the same clinic in Beauville. They all found that they had to pay amounts varying from $15 to $30 for medication to prevent mother-to-child transmission. KIJU brought this information to the attention of the police. This matter was investigated, and one nurse was arrested. Proceedings against her are continuing. KIJU undertook similar steps in respect of some other clinics, where they found that patients were also required to pay money to receive treatment for HIV and other illnesses. The police offi cial responsible for the investigation said they were hampered by the fact that there is a lack of resources to investigate and prosecute suspects for the crimes of corruption under domestic legislation. Early in 2004, the Kibunia legislature amended Kibunian legislation to incorporate into Kibunian legislation all the offences set out in article 4(1) of the AU Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption. Previously, corruption as such had not been criminalised, but theft and fraud had been criminalised.

15. KIJU approached the national courts for a declaratory order that Caroline should be accepted in a government-run child care institution. The application was brought in terms of the domestic Child Care Act (article 6) which stipulates, among others, that “children who have lost both parents shall be admitted to child care institutions in line with the principle of serving the best interests of the child, and taking into account the desirability of preserving the child as part of the extended family”. The Children’s Court found that it would be in Caroline’s best interest to remain integrated with the extended family. It also made reference to the fact that these institutions “were already overburdened, and that there were very few openings, only for very deserving cases” (quoting for the Court’s conclusion).

16. After the Children’s Court had refused the application, KIJU decided to take the matter further. It brought a further application, on behalf of Caroline, that:

- the death of her mother had been caused by the lack of a comprehensive health care programme comprising access to HIV medicines, given that such a healthcare programme is possible in the light of the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health (the Doha Declaration) and the Decision of 30 August 2003 on the Implementation of Paragraph 6 of the Doha Declaration and as such violated the Constitution;

- the rule according to custom which excluded her from inheriting was a violation of her right to equality;

- the refusal by the Children’s Court to grant her a place in a government-run child care institution is a violation of her constitutional rights;

- the lack of prosecution of nurses who commit corruption is a violation of her constitutional rights, in that it exposed her to the very real risk of contracting HIV (her status is unknown, and she has not shown any specifi c signs of disease).

17. KIJU brought the application to the highest court, the Constitutional Court. The Court held that KIJU had no locus standi to bring the fi rst issue on Caroline’s behalf because she was not the direct victim of this complaint. On the second issue, it held that the Constitution not only guarantees the right to equality, but also provides for the existence of customary law, in a provision (article 200) which states: “The existence of customary law shall be guaranteed.” (This provision is in the chapter on the judiciary, and not in the chapter comprising the Bill of Rights.) The third issue was determined on the basis of article 6 of the Child Care Act. The Court held that the provision itself was not attacked for unconstitutionality, but that the applicant’s argument pertained to the interpretation by the Children’s Court. The Court held that this interpretation cannot be held to be amounting to an unconstitutional refusal. On the fourth issue, the Court observed that the Constitution does not contain the right to development, the main legal pillars of the applicant’s arguments.

18. KIJU decided to submit the matter directly to the African Human Rights Court (in terms of article 34(6) of the Protocol establishing the Court), for its fi nding on these four issues.

19. The Registrar of the African Human Rights Court wrote to the parties, requiring them to address the following issues in their arguments:

- Should the Court deal with the matter in terms of Rule 81(a)?

- Does the alleged corruption constitute a violation of article 22 of the African Charter, or any relevant international law obligation of the state? Is this issue admissible before the Court?

- Does the lack of a governmental programme for HIV/AIDS treatment medication constitute a violation of the African Charter or any relevant international law obligation of the state? Is this issue admissible before the Court?

- Does the rule of primogeniture violate the African Charter or any relevant international law obligation of the state? Is this issue admissible before the Court?

- Does the government’s refusal to accept Caroline in an institutional care facility constitute a violation of the African Charter or any relevant international law obligation of the state? Is the issue admissible before the Court?

20. Answer these questions by way of heads of argument, prepared for both the applicant, KIJU (on behalf of Caroline Mabunda), and the respondent, the state of Kibunia.